By Ralph Loomis

Introduction

Highland bagpipers are usually informed, in no uncertain terms, what to do and how to do it by the pipe major. Understandably, in a pipe band, individual pipers are expected to conform to the group. But for those who play Scottish or Northumbrian smallpipes there’s considerably more leeway, particularly when it comes to tuning our drones. It can be done in a variety of ways, not only because common practice allows it, but also because the design of our drones can provide for it. To be meaningful, any discussion about drone tuning should also include discussion about chanters, scales, keys, intervals, and tonality. As individual pipers, it’s important to have a strategy for deciding how we want to tune our drones and why. Hopefully this article will assist readers in formulating some opinions. Some recorded examples are provided, and a partial listing of individual tunes is included for reference.

Tonality

For the sake of discussion, what is tonality? We can say it’s a tone or a combination of tones representing a set of structured relationships between a ‘home base’ (tonal center) and the tonal structures (chords, melodies & harmonies) that surround it. Tonality can be recognized by the particular scale or mode that defines its existence, but more importantly, by the progressions of chords derived from those scales or modes. In turn, scales and modes are defined by the position of specific intervals (whole steps and half steps) in between their relative scale steps. Tonal Centers (an individual note) provide the basis for scales, keys, and key signatures that more completely define a particular tonality. A scale is a series of notes moving stepwise from one tonal center to the next of the same name (the interval of an octave, or eight steps apart) . Flavors of tonality include Major, Minor, Modal, Chromatic, Diatonic, and Pentatonic. The bagpipe scale can produce most of these flavors but not the Chromatic.

Another term for tonality is Key (such as G major, A major, B minor, or D pentatonic). While individual notes have only one letter name, they can have more than one form, such as G# (called G-sharp, a half-step higher), Gb (called G-flat, a half-step lower) or G natural (meaning not G# and not Gb). Sharps and flats are sometimes called accidentals. Key signatures at the beginning of lines of music tell us which notes on that line will be sharped or flatted, thereby telling us what key(s) the tune is written in. Highland Bagpipe music usually has two sharps (F# and C#). Unless we do some finger magic to alter the notes, Scottish chanters generally produce Fs as F#s and Cs as C#s (though some Highland chanters and most Border Pipe chanters allow for alternative fingerings for alternative notes).

In music history, Modes refer either to the Greek Modes, in use by Plato’s time, or to the Gregorian Church Modes developed in the 8th and 9th centuries. Although many bagpipers think of our (bagpipe) scale relative to a Gregorian Mode (mixolydian), it actually has a more significant relationship to Pentatonic (5 note) scales, as I will demonstrate later.

For bagpipers, the pull of tonality may or may not be very strong based on each piper’s own personal experience. Any intuitive sense of good vs. bad or right vs. wrong in reference to tonality would likely come from a general perception of consonance vs. dissonance, i.e. whether music is either pleasing or unpleasing to the listening ear. Regardless, tonality could be considered analogous to magnetism for a physicist. While varying in degrees, it’s almost always there, exercising its influence for all time, whether we like it or not.

Origin of Current Highland Bagpipe Scale

Even for experienced analysts, tonality for a given piece of bagpipe music can be elusive. It can be difficult to determine what the scale is if a melody seems to disagree with cadence resolutions at the ends of the sections. To understand this better we need to look at the bagpipe scale more closely. From today’s perspective, many of us have used the explanation “it’s like a major scale with a lowered 7th step”, or “it’s just like mixolydian mode.” About 15 years ago I attended The College of Piping Summer School in Carlsbad, California. During a break between sessions I found myself walking along the pitch with that year’s Director, Dugald MacNeill. I asked if he would help me understand the bagpipe scale, referring to it as the mixolydian mode. In his inimitable style, he made it quite clear “it’s NOT mixolydian mode,” but rather the combination of three pentatonic scales, on G, on A, and on D.

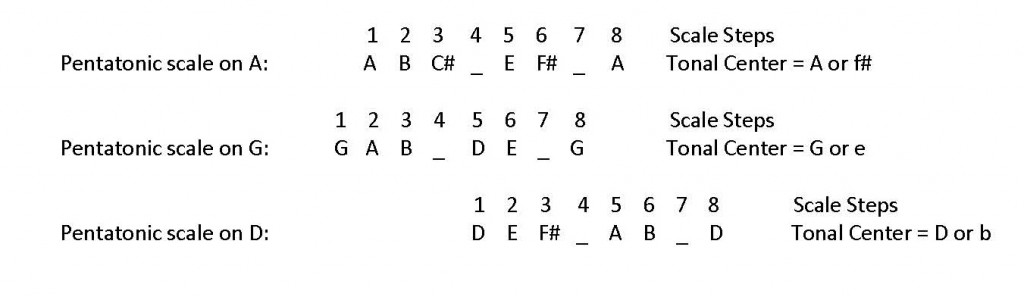

When we look at these pentatonic scales in the diagram below, notice that pentatonic (5-note) scales by definition have 2 fewer notes within the octave than diatonic (7-note) scales. Steps 4 and 7 are missing. Also notice that scale steps 1, 3, and 5 outline what we recognize diatonically as a major triad (interval of a major 3rd between steps 1 and 3, a minor 3rd between steps 3 and 5, and a perfect 5th between steps 1 and 5).

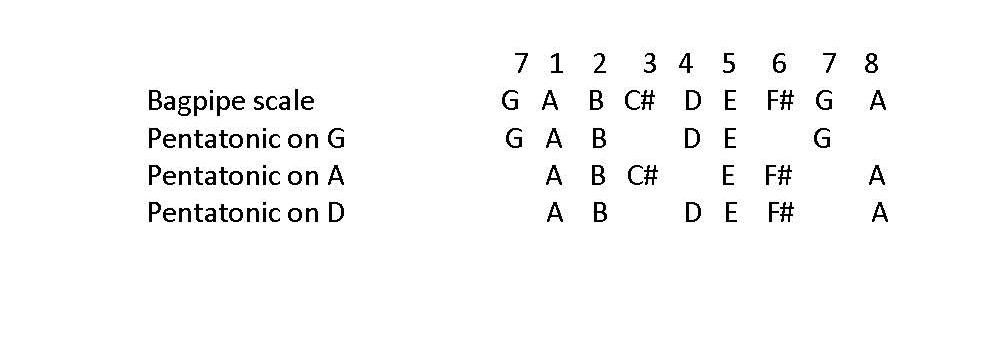

Now that you see the three pentatonic scales laid out, it’s easier to see how they line up in a very familiar way. With a new (assumed) set of step names, THIS is what we recognize as appearing to be mixolydian mode on A with half steps between 3 & 4 and between 6 & 7. In the 3 following lines we can see how all three pentatonic scales are available within the present bagpipe scale. Notice the scale on D has been rearranged because the D is in the middle of the chanter. Music for the ‘composite’ chanter can be derived from any of the 3 pentatonic scales indicated above and below, or from diatonic scales more familiar to us. To determine which scale, tonal center or key is indicated for a given tune, further analysis will be required.

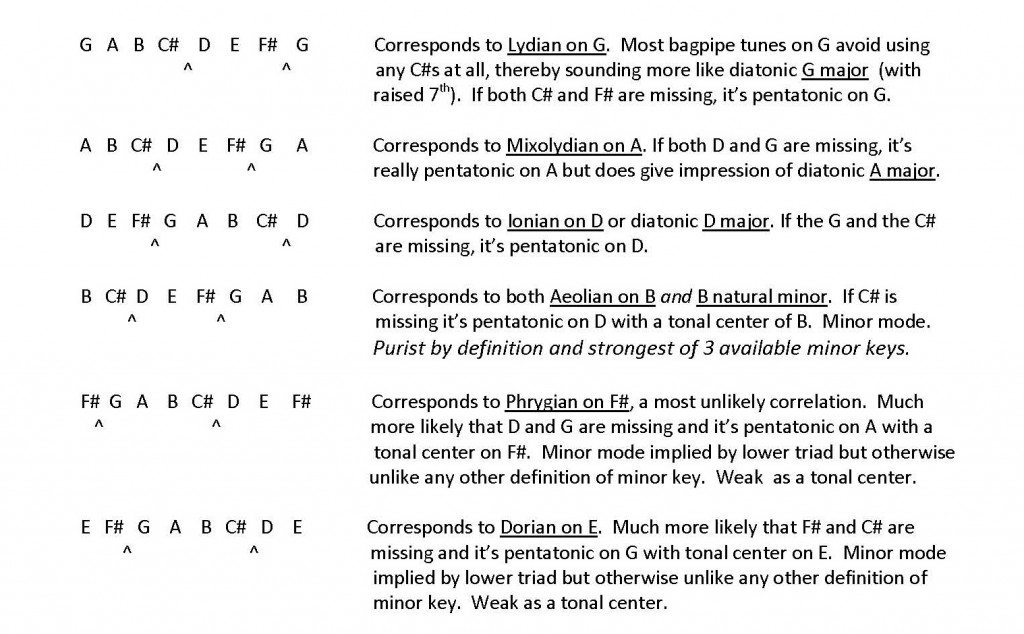

For the “composite” chanter, any scale whose lower triad (steps 1,3,5) is a major triad would be in a major mode. This accounts for scales on G, A, and D, same as for the 3 pentatonic scales. Any scale whose lower triad is a minor triad would be in a minor mode. This allows for scales on E, F#, and B. In the diatonic arena, these last three just happen to be the relative minor keys for the 3 major keys available on the chanter. With these six possible scales in mind we can know what possible tonal centers to look for in our search for tonality of a tune.

Given the 6 possible tonal centers we found above, we now should look at where the half steps occur (represented by the carat symbol). Notice they occur only between C# and D, and F# and G, regardless of the tonal center:

The relative strength or weakness of a tonal center relates to its pull or magnetism on our overall sense of tonality. Tunes written in “weak keys” seem nebulous in terms of where ‘home base’ can be found, whereas tunes written in “strong keys” leave us with little doubt in that regard. Another factor, not mentioned previously, is the implied harmonic progression of the melody. At the ends of regular phrases (normal resting places), what type of cadences (chord progressions) are used? Again, by definition this is determined by where the whole and half steps occur. To music theorists, cadences have specific definitions (perfect, imperfect, authentic, plagal, deceptive) and relative strengths associated with them.

Duncan Johnstone’s Complete Collection has many examples of tunes that use tonal centers other than the most common A pentatonic. One of the first things I notice is that in some tunes, scale steps are missing. This hints at the probability of a pentatonic scale, but which one? Using the descriptions above: If the tune contains any C#s then the scale will probably be pentatonic on A because it’s the only one of the 3 that contains C#; if there no C#s, look for F#s; If F#s are found, it’s pentatonic on D, otherwise it’s pentatonic on G. Of course if all notes are present in the scale of the tune (no scale steps missing), it’s more likely to be diatonic rather than pentatonic. To settle on a tonal center, look at the significant phrase endings and see how the cadences (implied harmonic progressions) resolve. One other method (not as conclusive) is to see if one of our available tonal centers (G, A, D, E, F#, or B) appears in a prominent position near the beginning and/or end of the tune. Unfortunately, this last method can sometimes be confusing because tunes don’t always start and stop according to any standard rule or pattern.

Premise

For Great Highland Bagpipes, the common practice is to tune the drones to (written) A only, regardless of the tonality of the tune. (One exception to this is found in Brittany, where Breton GHB pipers will often tune their drones to B when playing in B minor.) This is generally accepted as idiomatic for the performance style definition of Scottish Highland Bagpiping. The author has yet to hear a professional GHB performance or recording where the drones were tuned otherwise. If they were tuned to something other than written A, it just wouldn’t be considered ‘Scottish’.

For Scottish smallpipes, the drones are tuned to (actual) A and or D, and sometimes E. If a tune is in A, the A drone(s) will be used, but probably not the D as the note D doesn’t fit in the tonic chord (A, C# ,E) in this key, however an E would fit nicely. If a tune is in D, the D drone will most likely be used, but the A may also be used as it does fit in the tonic chord (D, F#, A) in that key. It is interesting to note that in this instance, drone tuning for the SSP that accommodates the tonality of the tune is considered no less ‘Scottish’ than drone tuning for the GHB. If a tune is in a key other than A or D, however, the drones are generally not tuned accordingly, but that’s not to say that they couldn’t be. Please see Examples For Listening section below.

My particular interest is in the very strong pull from the tonality of tunes in minor mode with a tonal center of B. This tonality can be significantly enhanced and strengthened by tuning the drones from A up to B.

For Northumbrian smallpipes, the situation is quite different. Firstly, the instrument often has 4 drones rather than 3, and each drone will probably have one or more tuning rings permitting at least twice the available number of drone pitches. In conjunction with keyed chanters, this instrument offers a much broader range of tonality for tunes. Therefore, we find a common practice for drone tuning that comes closest to representing the tonality of the tune. If the tonality happens to change in the midst of the tune, we may even find performers changing the drone tuning DURING THE PERFORMANCE to more accurately recognize the tune’s tonality. There’s even more than one way to accomplish this on the NSP. This practice for drone tuning represents a complete reversal from the practice of drone tuning for the Great Highland Bagpipes.

In conjunction with keyed chanters, this instrument offers a much broader range of tonality for tunes. Therefore, we find a common practice for drone tuning that comes closest to representing the tonality of the tune. If the tonality happens to change in the midst of the tune, we may even find performers changing the drone tuning DURING THE PERFORMANCE to more accurately recognize the tune’s tonality. There’s even more than one way to accomplish this on the NSP. This practice for drone tuning represents a complete reversal from the practice of drone tuning for the Great Highland Bagpipes.

Q & A

Q1: Is it technically possible for SSP drones to be tuned to pitches other than ‘A’? What pitches might be available?

A1: YES. Some pipemakers already provide for this so we know it’s possible. Length of tuning slides and design of drone reeds can provide for a broader range of tuning, but we also find the availability of tuning rings just as for NSP as an opportunity for alternative drone tuning. The most important thing to remember is if you already know you want to be able to tune drones to G, B, F#, or whatever, then ASK YOUR PIPEMAKER TO PROVIDE FOR THIS when you place your order. In many cases, they will do this, but not if you don’t ask for it. It may cost a bit more, but if that’s really what you want then it’s worth it to build in the capability from the outset. If your pipemaker doesn’t want to do this, then maybe you want to seek out a different pipemaker.

Q2: Let’s say for the sake of discussion you’re going to play 3 tunes, and it’s possible to tune your smallpipe drones either down to G or up to B. First tune in the lineup is Ann MacKechnie’s, which has a tonal center of G with the C# missing but the F# present. If you tune your drones down to G, the tonalities of the tune and drones are now in sync. The second tune is Rowan Tree with a tonal center of A and all scale notes included. Would we leave the drones in G? Probably not, as this would generate a clash of tonal centers (a whole step off) between tune and drones. We would probably bring the drones up to A. The third tune, Paddy’s Leather Breeches, has a tonal center of B and includes a low A and high G. Would we follow the pattern of matching tune and drones, or would it be more ‘Scottish’ to leave the drones tuned to A (a whole step off)? Or, would we simply do what most performers do and leave the drones in A throughout all 3 tunes, completely ignoring the issue of tonality for Ann MacKechnie’s and Paddy’s Leather Breeches? What would you do?

A2: These are theoretical questions and the theoretical answer is found somewhere in the balance between bagpiping tradition and tonality in music. Either we recognize the magnetism of tonality or we don’t. Either we exercise allegiance to bagpiping tradition or we don’t. The only available opportunity we have for doing both is when a tune has A as its tonal center. It becomes a dilemma whenever the tune does not have A as its tonal center. This becomes particularly apparent for me when the tonal center is B. As stated earlier, minor mode on B is the purest by definition and strongest of the 3 available minor keys. For you, personally, how strongly do you feel the pull of tonality?

The practical answer to these questions is that we wouldn’t want to put ourselves in the position of having to retune drones every time we go from one tune to another (although some smallpipers do), but then individual selections and program order might make it possible to group tunes accordingly by tonality.

Q3: Conceptually, is the ‘Scottish’ tradition ignored or enhanced by the alternative tuning of drones based on tonality of the tune? How can we tell?

A3: From a musical perspective it would be difficult to argue that tuning one’s drones to match the tonality would not be considered an enhancement. The clarity, strength, and relative consonance of matching tonalities between tune and drones are unmistakable. An overall sense of a tonal home base is much more evident and the occurrence of the more dissonant intervals is diminished.

In the highland piping tradition, the only thing that tradition allows is drones in A. Whenever a tune is not in A (or D), inherent clashes of tonality become evident, any sense of tonal home base becomes obscured, and a sense of disharmony is apparent. Under these circumstances, if the drones happen not to be in tune, then matters are made considerably worse.

All we have to do is listen to some examples of alternative drone tunings for the same tune and determine if it sounds better or worse, stronger or weaker, more idiomatic or less idiomatic. Ultimately an opinion will evolve about which example we like best. Later in this article under the heading Examples For Listening, some recorded examples are provided for you to hear.

Technical limitations for Scottish smallpipe drone tuning

If drones do not provide a sufficient range of extension to allow tuning up to B and down to G without a negative effect on tone quality, then we have to revert to working with drone reeds to achieve the desired result, and even that can be insufficient. By design, some instruments can be retuned successfully already. This means that at least some pipemakers are willing to build in this capability.

We don’t really want to be swapping out drone reeds during a performance to enable drone retuning. Both single blade and double blade reeds are found in today’s Scottish smallpipe. Single blade drone reeds produce a more stable pitch, but then are more difficult to adjust for pitch variation. Bridle position and seating position in the drone are the remaining variables. Double blade drone reeds produce more variability in range of pitch, can easily be adjusted for length to alter pitch, but perhaps are less stable depending on strength of resistance. If appropriate drone extensions are not an option, work with different drone reeds to achieve desired results.

Generally, tuning rings (as for Northumbrian smallpipe drones) are an excellent way to enable alternative drone tunings. Northumbrian pipemakers have been very successful in this regard, and some (but not as many) Scottish smallpipe makers have produced them as well. The nice thing about this option is that it is much easier and potentially less expense to add after the fact.

The Best of Two Worlds for Smallpipers

Because of my interest in the wider variety of available tonalities and drone tunings, I play a set of Colin Ross Northumbrian smallpipes in D with a 16-key Northumbrian chanter, and alternately a Scottish smallpipe chanter made for use in the same chanter stock. My instrument has 4 drones, primarily tuned (from the bottom up) to A, D, A, D. Both A drones have tuning rings that allow for tuning to B, and both D drones have tuning rings that allow for tuning to E. In addition, the tuning slides have sufficient length to almost be able to tune up or down a whole step without having to use tuning rings. I do have to adjust the reed bridal if I want to tune an A down to a G (that’s what I did to produce the listening example Ann MacKechnie’s for this article). This allows for the easy swapping of chanters and repertoires from one medium to the other. The same freedom for drone tuning for Scottish smallpipe drones is achieved by the use of tuning rings.

Conclusion

I am in favor of primarily recognizing the tonal centers of G, A, B (in particular), D, and E by tuning my drones to those pitches. By keeping the tonality of drones in sync with the tune, the idiomatic character of the result is considerably enhanced. To some listeners, it can be quite a distraction to listen to a bagpipe performance when the drones present a constant clash of tonalities with dissonant intervals and disharmonies. If Northumbrian smallpipers can successfully tune their drones accordingly, and they do, I can think of no reason why Scottish smallpipers shouldn’t be able to do the same just as successfully. Try it. You might even like it.

Examples for Listening (mp3 files)

Ann MacKechnie’s, Iain MacDonald (drones in A, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Ann MacKechnie’s, Iain Mac Donald (drones in G, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Farewell To Nigg, Duncan Johnstone, (drones in A, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Farewell To Nigg, Duncan Johnstone, (drones in B, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Farewell To Barra, Duncan Johnstone, (drones in A, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Farewell To Barra, Duncan Johnstone, (drones in B, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Paddy’s Leather Breeches, (drones in A, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Paddy’s Leather Breeches, (drones in B, Ralph Loomis, home recording)

Partial Bibliography of Tunes in Minor Mode Found in Published Repertoire with Tonal Center of

B or G (Tunes in G Identified by Asterisk)

Duncan Johnstone “His Complete Compositions”, Shoreglen Ltd, 49 Moray Place, Strathbungo, Glasgow, G41 2DF, Scotland, U.K. (* indicates Major Mode, tonal center of G)

Farewell to Nigg

Mrs. Mary Anderson of Lochranza

Dominic McGowan

Fr Donald’s Burach

Duncan’s Salute to Ross and Gretta

Isa Johnstone

Farewell to Arran

Isobelle MacLean

Dr. Jimmy Campbell’s Welcome Home

James MacLellan’s Favourite

Carolyn Spohn

Jock Anderson of the Glen

The Isle of Barra March

Romany

Meg MacRae

Lt. McGuire’s Jig

Farewell to Barra

* Ann Marie Campbell’s March

* Finlay MacDonald

* Ian Eosa’s return To Vatersay

* Seonaid

* Janet’s Jig

* Guido Margiotta

Standard Settings of Pipe Music of The Seaforth Highlanders, 1998 Edition, Paterson’s Publications, 8/9 Frith Street, London, W1V 5TZ, England, U.K. (* indicates Major Mode, tonal center of G)

Cutty’s Wedding

The Ale Is Dear

The Isle Of The Heather

Cuidich’n Righ, N. McSwayde

The Mist Covered Mountains

Greenwood Side

Craig Miller Castle

The Glasgow Gaelic Club

Dark Lowers The Night

Wha’ll Be King But Charlie

* O’er The Moor Among The Heather

* The Sons Of The Mountains

Philharmonic, Murray Blair, 1998, Bulk Music Ltd, 9 Watt Road Hillington, Glasgow G52 4RY, Scotland, U.K.

(* indicates Major Mode, tonal center of G)

Ross’s Farewell To Pangnirtung, Murray Blair

Bottle Eyes, Murray Blair

The Piper’s Black Dog, Murray Blair

Demtel Schizophrenia Kit, Ian Lyons

The Radar Racketeer, Adrian Melvin & Murray Blair

Flogging The Riff, Murray Blair

The Slick Diamond Back, Murray Blair

Infliction, Murray Blair

The Road Runner, Ian Lyons

Jenny’s Chickens, Arr. Murray Blair

DV8ing Again! , Murray Blair

Advance To The East, Murray Blair

* Thick Planks, Murray Blair

The Antipodes Collection, Volume One, Mark Saul, 1993, ISA Music, 27-29 Carnoustie Place, Scotland Street, Glasgow G5 8PH, Scotland, U.K.

Brian Symington, Mark Saul

Piping Hot, Mark Saul

Me Clootch is Awee! , Mark Saul

Kopenitsa, Mark Saul

Going Steaming, Mark Saul

The Hell Bound Train, Mark Saul

Pump It Out, Mark Saul

The Antipodes Collection, Volume Two, Mark Saul, 1993, ISA Music, 27-29 Carnoustie Place, Scotland Street, Glasgow G5 8PH, Scotland, U.K.

Sub Zero, Mark Saul

Bronni’s Blue Brozzi, Mark Saul

Gondola Wedding, Danny Edwards

The Master Piper Nine notes that shook the world, A Border Bagpipe Repertoire, William Dixon 1733, Presented by Matt Seattle, 1995, Dragonfly Music, 10 Gibson Street, Newbiggin-by-the-Sea, Northumberland NE64 6PE, U.K.

The New Way To Morpeth

Little Wee Winking Thing

Pipe Major Robert Mathieson “MARKING TIME”, Book One, 1990, ISA Music, 27/29 Carnoustie Place, Glasgow G5 8PH, Scotland, U.K.

The Border Reel, R. Mathieson

Ian’s Wedding, R. Mathieson

The Opal, R. Mathieson

Pipe Major Robert Mathieson “About Time Two”, Book Two, 1996, ISA Music, 27/29 Carnoustie Place, Glasgow G5 8PH, Scotland, U.K.

The Branch Salute, R. Mathieson

Flee The Glen, R. Mathieson

Fair Maiden’s Prayer, Traditional

The Irish Chase, R. Mathieson

The Chapel Hill Hornpipe, S. McCawley

Jack Bettridge, R. Mathieson

The ‘Unwelcome’ Reel, D. Barnes

Piper Of The Year, C. Djuritschek

Pipe Major Robert Mathieson “Taking Notes”, Book Three, 1996, ISA Music, 27/29 Carnoustie Place, Glasgow G5 8PH, Scotland, U.K.

The Nine Of Diamonds, R. Mathieson

Henderson’s Reel, R. Mathieson

Pay The Piper, S. McCawley

The Celtic Matador, D. Ogilvie

Charlie Macdonald, D. Ogilvie

The Spanish Piper, D. Ogilvie

Ghillies In the Bucket, Allan Clark

Pipe Major Robert Mathieson “The Fourth Title”, Book Four, 2003, The Kilt Centre, c.o. The Pipe Box, 1 Campbell Lane, Hamilton, Scotland ML3 6DB, U.K.

Medieval Dance, Al Clarke

Eat the Beat, R. Mathieson

Swinging Folk, R. Mathieson

The Herb Man, C. Djuritschek

Gordon Duncan’s Tunes, 2007, The Gordon Duncan Memorial Trust, c/o Greentrax Recordings, Cockenzie Business Centre, Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie East Lothian, EH32 OHL, Scotland, U.K.

The Soup Dragon, Gordon Duncan

The Thin Man, Gordon Duncan

The Sleeping Tune, Gordon Duncan

Zeeto The Bubbleman, Gordon Duncan

FIRST BOOK, Neil Dickie, 1983, 10th Edition – 2000, Hays Productions Ltd., Marketed by Scott’s Highland Services Ltd., 143 Stronach Cres., London, Ontario N5V 3G5, Canada

Nancy Lee, Neil Dickie

Mrs. Gladys MacDonald, Roderick MacDonald

Ann Gray’s Collection, Music for the Great Highland Bagpipe, 2000, Ann Gray, 6607 Coach Ridge Rd. S.W., Calgary, Alberta, Canada, T3G 1J6

Al MacDonald’s Practice Table, John Toohey

Kit’s Reel, Charlie Glendinning

Pipe Major Ian Whitelaw, Sean Somers

B. C. Pipers’ Gathering 1986, Ian MacDonald

The Boys of 101, Ann Gray

The Broadview Burgler, Ann Gray

The Robinsons of Twin Ponds, Ann Gray

Kelvinaugh Street Spirits, Ann Gray

Jeff Brewer Of Portland, Ann Gray

Kelvinaugh Street Spirits, Ann Gray

Pipe Major Rob Laing, Ann Gray

Captain Wawa, John Toohey

Fraser Lloyd, Ann Gray

The Ramsay Man, Ann Grey

The Fred Morrison Collection, Fred Morrison, 2006

New Year’s Day, Fred Morrison

The Big Picnic, Fred Morrison

The Irish Embassy, Fred Morrison

The Lochaber Badger, Fred Morrison

Cathy Anne MacPhee’s, Fred Morrison

Lochaber to Argyll, Fred Morrison

Irish Tunes old & new, Terry Tully, 2001

The Otter’s Holt, Arr. Terry Tully

Condons Frolics (2), Arr. Terry Tully

Terry Tully Collection of Traditional Irish Music, Terry Tully, 1991

Eyebrows, Terry Tully

The Connaught Man’s Ramble, Arr. Tommy Tully

The Big Ship (Reel), Arr. Terry Tully

The Big Ship (Jig), Arr. Terry Tully

Terry Tully Collection of Traditional and Contemporary Irish Music, Book Three, 1997

The Valley of Knockanure, Arr. Terry Tully

The Bouncing Czech, Gerry Hanlon

The Whisky Bus, William Garrett

SCOTS GUARDS Standard Settings of Pipe Music, Volume I, 5th Edition, 1965, Paterson’s Publications Ltd., London, England (* indicates Major Mode, tonal center of G)

# 8 Greenwood Side

# 77 The Heights of Mt. Kenya or Pangani Corner, Pipe Major R. L. Kilgour

# 113 Master James M. Diack, Pipe Major W. Ross

# 114 The Reverend Alan Davidson, Pipe Major J. B. Robertson

# 116 Windsor Castle, Pipe Major R. Crabb

# 151 Loch Monar, Pipe Sergeant W. Ross

#152 Leaving Ardtornish, Pipe Major W. Ross

# 288 The Braes of Mar

# 320 Struan Robertson

# 341 The Ale Is Dear

#394 Dark Lowers The Night, Pipe Major J. Mackay

#400 The Heroes Of Vittoria, J. Maclellan

#438 The Isle Of The Heather

#443 Fair Young Mary

#484 Paddy’s Leather Breeches

* #485 The Shaggy Grey Buck

SCOTS GUARDS Standard Settings of Pipe Music, Volume II, 4th ( Revised) Impression, 1992, Paterson’s Publications Ltd., London, England

# 551 Angus Mckinnon, Pipe Major D .S. Ramsay, BEM

# 559 McCloud of Mull, Pipe Major Donald MacLeod, MBE

# 577 Lieutenant Colonel D. J. S. Murray, Lieutenant J. Allan

# 644 Farewell to Nigg, D. Johnstone

# 654 Captain Colin Campbell, Pipe Major Donald MacLeod, MBE

# 666 Wiseman’s Exercise, Pipe Major C. Campbell

# 679 Lieutenant Colonel D. J. S. Murray, Pipe Major A. Macdonald

# 691 The Ness Pipers, Pipe Major I. Morrison

# 728 Leaving Lochboisdale, Pipe Major J. Wilson

#755 McGuire’s Jig

FEADAN MOR The Mac Harg Collection, Book One, Iain Mac Harg, 2002, Clan Mac Harg Music, 1611 VT Route 232, Marshfield, VT 05658, U.S.

Suite 316, Iain Mac Harg

The Unlucky Piper, Tyler Matteson, Arr. Iain Mac Harg

Cabot Trail Fire House, Iain Mac Harg

Ag Iomradh eadar Ile’s Uibhist, Traditional

C.P. Air Pipe Band, Jack Lee

Echoes of Glencoe, Chuck Murdoch

The Bone Place, Marc Dubois

Earl Mac Harg’s Jig, Iain Mac Harg

Feadan Mor (The Big Chanter), Iain Mac Harg

Mike and the Antipypr, Iain Mac Harg

Acknowledgements:

Many thanks to my wife Pam for her musical judgment, to my daughter and husband Vivian and David for assistance with proofreading, to Glenn Dreyer for asking me to do this, and to Glenn Dreyer and Nate Blanton for their considerable effort to read and comment on all of these ramblings.

COPYRIGHT 2011 RALPH R. LOOMIS

Ralph Loomis holds an undergraduate degree in Performance and Pedagogy of the Clarinet, a graduate degree in Music Theory and Composition, professional experience as clarinetist in various symphony orchestras and wind ensembles, teaching experience with students of the clarinet, computer programming languages, and most recently the bagpipes (GHB and SSP). He served for several years as pipe major of a highland pipe band in California, and currently is actively involved with two different smallpipe groups in Central New York. At this point, his greatest enjoyment with music is derived from playing smallpipes (SSP and NSP), working and performing with other smallpipers, and seeking out and arranging appropriate music for smallpipe performance.