Click here to download a copy of the original scanned journal

JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS

NUMBER 7 JULY 1994

CONTENTS

QUOTATIONS…………………………………………………………………………………..3

FROM THE EDITOR…………………………… 5

FOR YOUR INFORMATION……………………….6

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR……………………….7

CHARACTERISTICS AND AVAILABILITY OF SUITABLE TIMBER SPECIES IN RELATION TO THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE MANUFACTURE OF SCOTTISH BAGPIPES; by David Moore……………………………………………………9

AMERICAN WOOD FOR AMERICAN MADE BAGPIPES………………..15

A BORDERLINE (PIPE) CASE; by Alan Jones…………………16

THE PHAGOTUM AND WILLIAM COCKS; by Eoghan Ballard…….26

REGARDING THE STANDARDIZATION OF UILLEAN PIPES; by Bruce Childress……28

THE SCOTTISH TRADITIONAL MUSIC TRUST; by Gordon Mooney………32

REVIEWS:………………………………………………………………………………………….34

– Shores of Lake Champlain, cassette

– Toodle-Oodle Bagpipes, Chosen by Julian Goodacre

– The History of James Allan

– Reed Design for Early Woodwinds, by David Hogan Smith

– The Rumblin’ Brig, by Hamish Moore

– Farewell to Decorum, CD by Hamish Moore and Dick Lee

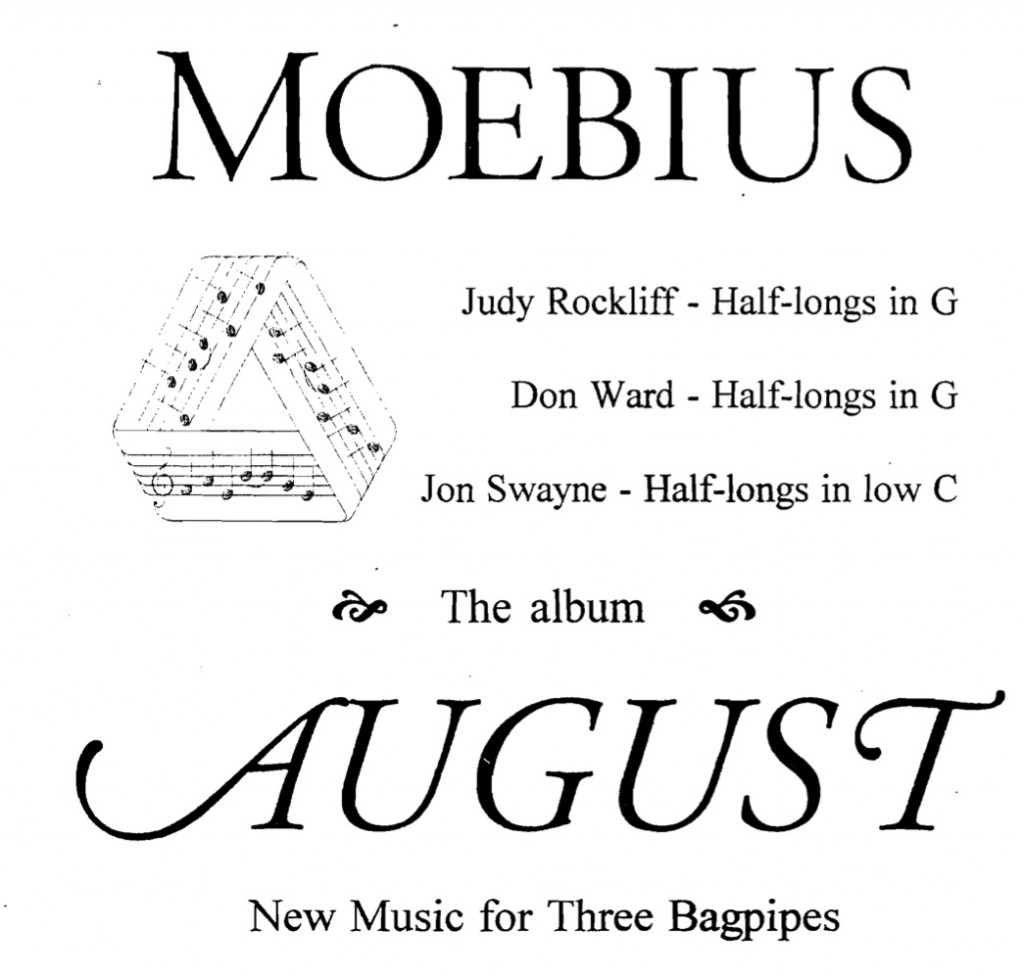

– August, by Moebius

QUOTATIONS

“Hell is full of amateur musicians.”

– George Bernard Shaw

The following were taken from (a) The Poetry of the Pipes and (b) The Northumbrian Smallpipes, both compiled by Keith Proud and Richard Butler in 1983:

“Thomas Cowley, a Lowland and Northumbrian pipemaker, leapt from the Newcastle bridge for a wager and drowned. “

(b) Newspaper report of 5/9/1838

“AII save the shepheard, who for fell despight

Of that displeasure,broke his bag-pipe quight.”

(a) The Faerie Queen, Edmund Spencer 1596

“Here lies dear John, whase pipe and drone, And fiddle aft made us glad;

Whase cheerfu’ face our feasts did grace A sweet and merry lad. “

(a) Epitaph for John Hastie, Jedburgh Town Piper, c.1731

“… Whene’er his pipe did silence break, You’d thought the instrument would speak.”

(b) John Sykes ‘Local Record’, 1821 in reference to William Cant, who played violin and Northumbrian pipes. He played Northumbrian pipes in the American war of Independence.

“...playing the bagpipes within doors is a Lowland and English custom… “

– From General Stewart of Garth, ca. 1820.

“The pipes’s sweet air made all as gay as June,

The Way to Wallington was still the tune. “

– From Thomas Whittell, c. 1750, describing festivities at Shaftoe Crag, near Wallington.

3

MORE QUOTATIONS

“There in the humbler mood of peace, he stands;

Before him, pleas’d, are Seen the dancing bands.

In mazy roads the flying ring they blend,

So lively frame’d they seem from earth t’ascent

Four gilded straps the artist’s arm surround;

Two knit by clasps, and two by buckles bound.

His artful elbow now the youth essays,

A tuneful squeeze to wake the sleeping lays.

With laboring bellows thus the smith inspires

To frame the polished lock, the forge’s fires. “

– From “The Maid of Gallowshiels” by William Hamilton of Bangour (1704-1750).

…“It takes him whiles an afternoon

Ere he can get his pipes in tune,

And when that he his best has done

And no succeeds,

He curses him that made the drone,

And damns the reeds.

To see him wi’ his instrument,

Ye’d laugh till ye were fairly spent,

To hear the lolling, loud lament

That he does make.

Ye’d swear his leathern bag wad rent, and bellows break.

His bellows was a smiddy suit,

His drone’s a yard without dispute.

His chanter is, I think twa foot, and something mair,

But when it opens its noisy throat,

‘Twad flay a bear”…

…He plays ‘The Scots came o’er the border’,

‘The Selkirk sooters’, and ‘Whigs in order’,

But mixes them in sic disorder

Wi’ ‘Fisher lad’, Baith drones and chanter cry out murder!

It’s ‘Music mad’.

… Gie him his due – I’ve heard him tell

He only plays to please himsel,

Dull melancholy to expel,

Being rather nervous;

But frae his chanter’s dismal yell

The Lord preserve usl… “

– From a poem by John Farrer, 1831, in which the playing of Thomas Hair, of Bedlington, is compared to an un-named piper of little talent – it is the latter piper referred to in the above stanzas.

4

FROM THE EDITORS

Welcome to the 7th Journal of the NAALBP. In this, the last issue that Michele and I will be able to complete, we have a banner number of reviews and articles, thanks to the contributions of our members, whose numbers have increased steadily through these five years. The state of bellows piping is very healthy indeed, judging by the number of players, makers, workshops, tunebooks, and accessories available at the present time. We flatter ourselves to presume that the Journal has been helpful to those beginning Lowland piping and has become a resource for those who are well along in their exploration of Scottish bagpiping. The rise in interest has spawned a small marketplace around Lowland piping, and the novice today has at his or her disposal any number of touchstones available in short order – quite a different state of affairs from the way things were back in the early 80’s. For example, the efforts of Gordon Mooney and Hamish Moore, through their classes and recordings, have gone a long way towards imparting solid repertoire and style in the playing of the Scottish smallpipes and Lowland pipes. Their visits to North America have provided the living contact we require as we develop our own tradition. The efforts of piping event coordinators such as Alan Jones, George Balderose, Brian McCandless and others have provided venues for the gathering of Lowland pipers. So, although our continent is enormous and many pipers are dispersed, we have overcome isolation in our pursuits thanks to the vast amount of networking which has occurred in the past decade.

Having said that, I feel that the first phase of the NAALBP has been successfully completed – providing basic information and linking pipers together through its semi-annual publication. However, it is now time for Brian and Michele to step off and pass the torch along. This is because increased work responsibilities and professional time commitments have severely limited the time and effort that we can dedicate to the production of the Journal. As you may be aware, our membership is nearly 200, and management of the mailings and financing is equally time-consuming. Thus, we are unable to meet our obligation of completion of Journal 8 and wish to pass the whole shebang over to another responsible party in the coming year. To effect a smooth transition, we need interested members to contact us by mail or phone to discuss the details of Journal production. Our main concern is in locating a group or a person who is willing to put in the time and effort required to maintain a reasonable level of production quality and neutral authority. I need to know if you will be willing to let Michele and me make the decision on who will assume responsibility – or do we need a formal vote within the organization? Let us know. For our part, we would like to remain contributing editors and would like to continue to organize a yearly event in the mid Atlantic region.

Brian and Michele would like to acknowledge and thank the following people for their inspiration and assistance throughout the formation of the NAALBP and the production of the Journal: Alan Jones, Mike MacNintch, Tom Childs,Michael MacHarg, Richmond Johnston, Sam Grier, Nate Plafker, Steve Bliven, Michael Dow, John Dally, John Creager, Sandy Ross, Laurie Franklin, James Coldren, Jean-Luc Matte, John Addison, Dave Van Doorn, and Julian Goodacre. Thank you also to the contributors to the Journal, too numerous to name, but who have been much appreciated all the same. We hope that the members of the NAALBP will exhibit interest in sustaining this organization, difficult though that is on such a large continent. Good piping, and keep in touch.

Brian and Michele McCandless

5

FOR YOUR INFORMATION

From the Internet

1) As we mentioned in Journal 6, there is a very active computer discussion group for bagpipes that is a wealth of up-to-the-minute information and correspondence. Two recent discussions that your editor participated in concerned bellows bagpipe history and bagpipe wood seasoning and maintenance. Other discussions have included specifics of reed making and adjustment, origins of Highland bagpipe fingering movements, and biographies of pipers and pipemakers. If you have a computer with a modem and can access Internet, then you can subscribe to the Bagpipe discussion group by sending your request to join to:

pipes-request@sunapee.dartmouth.edu.

2) Richard Shuttleworth reported on 13 May 94 that he was sent a postcard of a painting which hangs in the Bytown Historical Museum, Ottawa, Canada showing a man seated on a stool, in a pastoral setting, playing a set of Uillean pipes, apparently a practice set with no drones or regulators. The back of the postcard carries the inscription:

“John Peter Pruden (1778-1868) with Irish bagpipe. He advanced in the Hudson’s Bay Co. from 13 year old apprentice to chief factor at the Carlton House, Northwest Territories. Portrait by W. C. Forster.”

3) Nick Whitmer suggests that pipers and others interested in traditional music may wish to read the book The Little Country by Charles de Lint (William Morrow, 1991). It is a fantasy novel, the genre created by J. R. R. Tolkien with his Lord of the Rings trilogy. Most of The Little Country takes place in modern-day Cornwall with traditional music as an important part of the story. The main character is a fiddler/Northumbrian piper; the chapter titles are tune names; and there are a few pages of tunes – composed by Mr. de Lint – at the back.

New Pipemakers

We have learned that Sam Grier and Peter Riley have joined forces as Riley-Grier, makers of bagpipes. Sam tells the editor that they are planning a line of hybrid pipes (for flexibility in playing) executed in a synthetic material for stability.

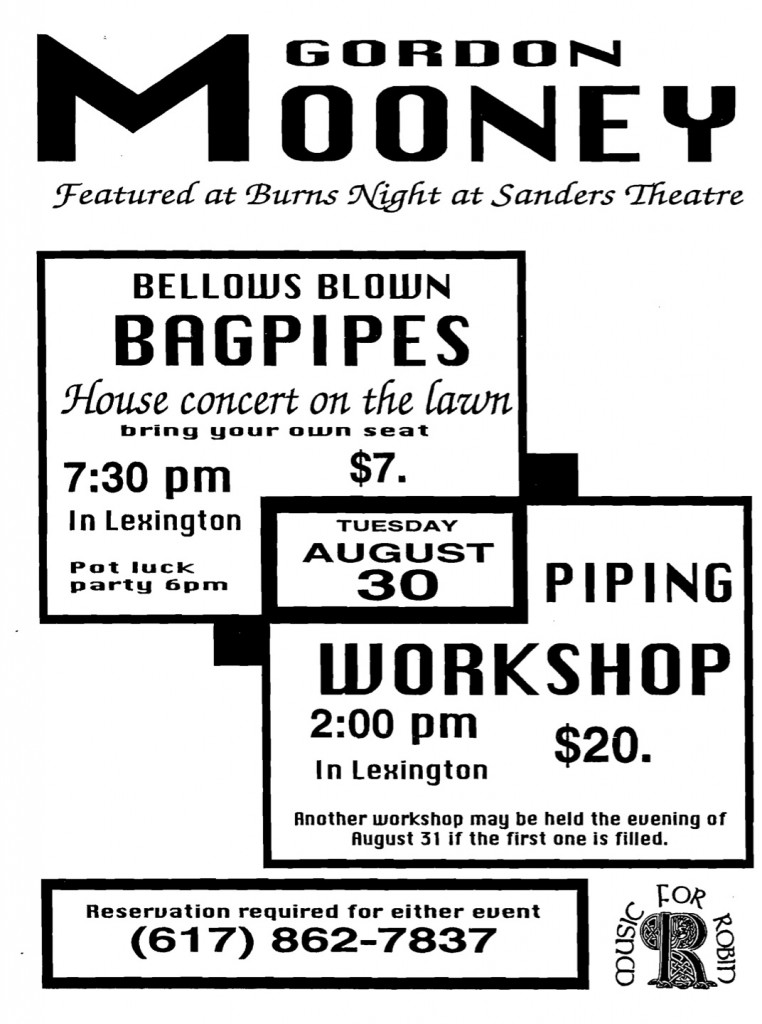

Mail Order Catalog

Gordon Mooney has a mail order catalog company – The Pipe Case – which is the most comprehensive we’ve seen for Lowland pipe supplies, books, and recordings. You can get a catalog by writing to Traditional Music, Piperscroft, 1 Hazeldean Meadow, Newstead, Melrose, Roxburghshire, Scotland, U.K. TD6 9DZ.

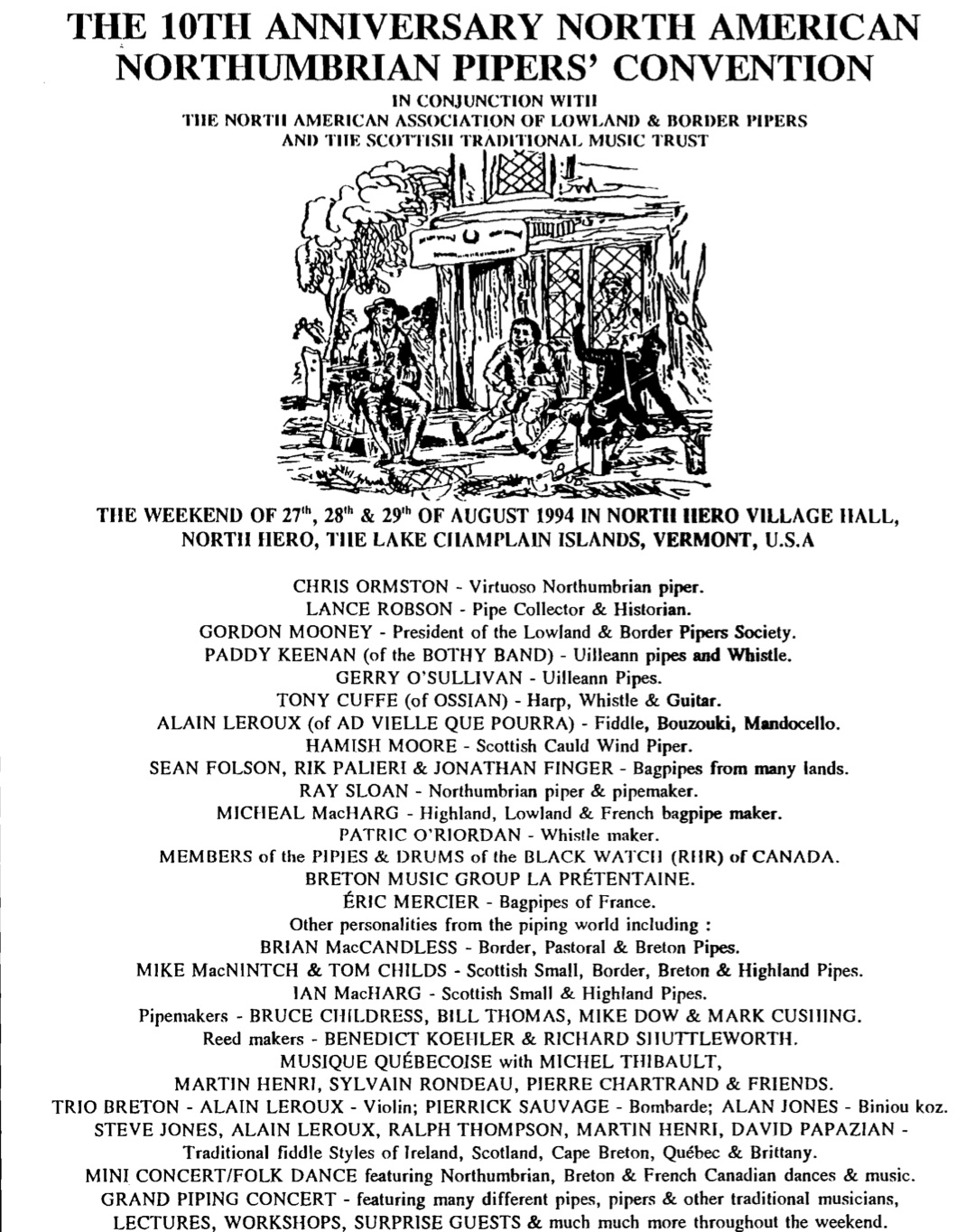

Pan’s Fancy

For those of you who enjoyed their playing at Pipers’ Day 1993 and meeting with Edwin George at this year’s Pipers’ Day, we are pleased to announce that their first compact disc is coming soon. Also, they will be appearing at the North Hero Convention August 27, 1994; and at the Pennsbury Manor Fair in Morrisville, PA on September 10th and 11th. For more information, call or write Pan’s Fancy (215) 482-2773 c/o 232 Dupont Street, Philadelphia, PA 19127.

6

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Brian, a charaid:

Your March 1993 and September 1993 issues were, as usual, very interesting. In earlier issues, some smallpipers seem to have been resentful of the fanfarron which goes on amongst players of the piob mhor, and were critical of the rigidity of instruction and methodology to which all players of the piob mhor are subjected to today. I would remind those critics that over 150 years ago such “standardization” did not exist, and that a minority group of piobairean exist today which uses the “alternative” method of playing the piob. This method, of course, does not have the freedom of fingering which appears to exist among players of the small pipes or, for instance, those of the gaita gallega o asturiana…but freedom of expression in the ceol mor is frequent along with some older gracings e.g., the “redundant A” in use with the turludh and creanludh; the semi-closed high G; and the “open C”. Naturally, the orthodox majority is appalled at this deviation from what it considers the one and only way to play the music of the piob mhor.

My small pipe is from Heriot and Allan and has the B flat chanter with an extra metal key on the top hand. Certain doublings do not come off well on the smallpipe…like turludh and creanludh…but individual gracings are very satisfactory. I envy all you pipers who can play various kinds of pipes. I would find it hard to change my Highland fingering.

David V. Kennedy, Sacramento, CA

To All NAALBP Members:

There is a good wood supplier, called TRADE WINDS, in the northeastern part of the United States, who can supply most or all of the woods associated with pipe making. For example, they carry Cocobolo, Honduras rosewood, Brazilian rosewood, tulipwood, French (Pyrenees) boxwood, Castella boxwood, black African ebony, and others. Their proprietor is Dave Muelrath, and if you call, tell them that Michael MacHarg told you about them. Trade Winds can be reached at: Trade Winds, Dave Muelrath, HCR Box 64, Grafton, VT 05146 (802) 843-2594.

Yours Aye, Michael S. MacHarg, Box 286, RFD 2, Rt. 14, So. Royalton, VT 05068

Gentlemen:

May I call the readers attention to page 23 of the June 1992 Journal and the article entitled “18th Century Long Pipes” by Denis Brooks. In this article the author gives the following as rather factual information regarding the Irish great drone, mouth blown bagpipe (which he erroneously refers to as a “war pipe”.) The pipe had two drones, the shorter was an octave higher in pitch, its range was nine notes, its range was from a’ to a”, there was a g’ below the a’, and the drones were tuned to a and A. However, nothing is known about this instrument which fell from use in the 17th century. A last remaining example, said to date from the 1745 period, was in the Musee de Cluny in Paris. However, it was mysteriously lost and the museum refuses to comment on it and has no measurements nor photos! As far as is known, no one has seen it since the 1940’s and those who had seen it prior, in the bad good old days, never bothered to study nor write about it!

The mouth blown bagpipe was never referred to in Ireland as a “war pipe” until the 1930’s when the Irish Pipe Band Society, seeking a more ancient tradition for its newly adapted great Highland Bagpipe, began to use the term.

Sincerely, Frank Timoney, Bayport, NY

7

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR (continued)

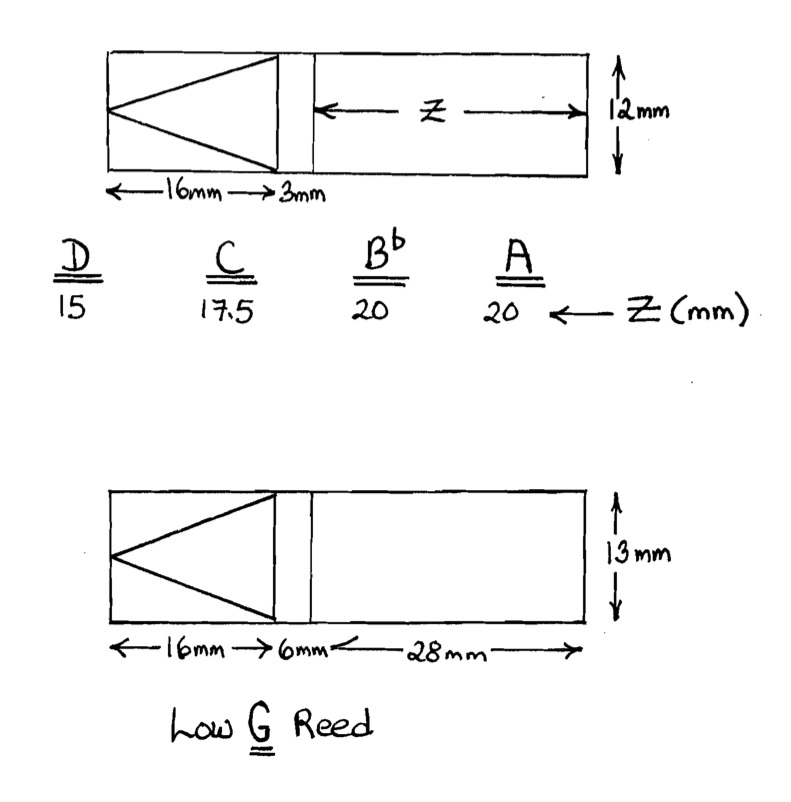

Dear NAALBP Reedmakers:

Having now made literally hundreds of plastic chanter reeds I have refined my designs to the point of needing to modify my article published in Journal 3. I now use 12 mm for the width of all smallpipe reeds, except for low G which remains at 13 mm. Based on Colin Ross’ standardized smallpipe chanter reed design published in the Northumbrian Smallpipers’ Magazine I submit the following designs:

The staple design has changed slightly in that the eye or oval should be more open, the narrow dimension being about 4 mm. You should experiment with this dimension to affect the overall volume and strength of the reed.

I now add 1 mm to the length of the blades to facilitate easier manipulation during tying-up. Afterwards, you can trim the reed easily to the desired length and squareness. For bridles I now use orthodontist rubber bands, although the two-wrap wire bridle also works well. To seal the wrapping I use a water based urethane – it dries quickly and is easy to clean up. I apply it with a q-tip.

Yours, Michael MacHarg, Box 286, RFD 2, Rt. 14, So. Royalton, VT 05068

8

The Characteristics and Availability of Suitable Timber Species in Relation to the Past, Present, and Future Manufacture of Several Forms of Scottish Bagpipes1

by David Moore2

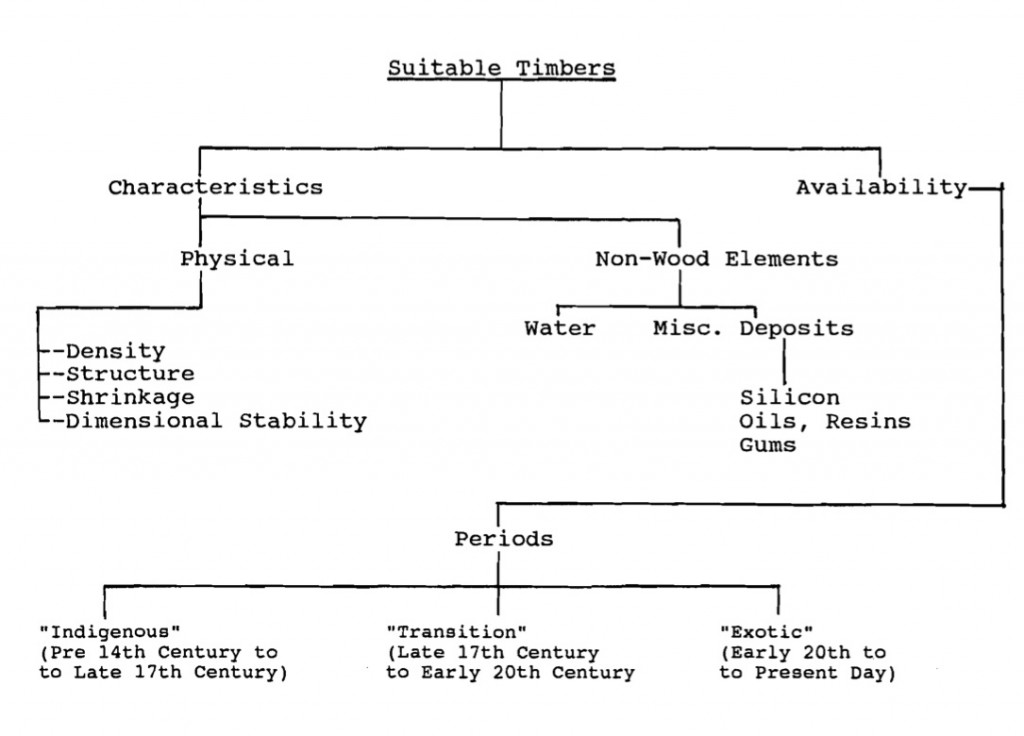

The characteristics of suitable timbers for the manufacture of bagpipes can conveniently be divided firstly into those physical features which arise from the nature and arrangement of the cell structure of the timbers and secondly from the presence of other materials which, for the moment, we shall refer to as MISCELLANEOUS DEPOSITS (see Appendix I).

There are four main PHYSICAL properties to consider, bearing in mind that none is absolute in itself and that one characteristic may modify one or more of the others.

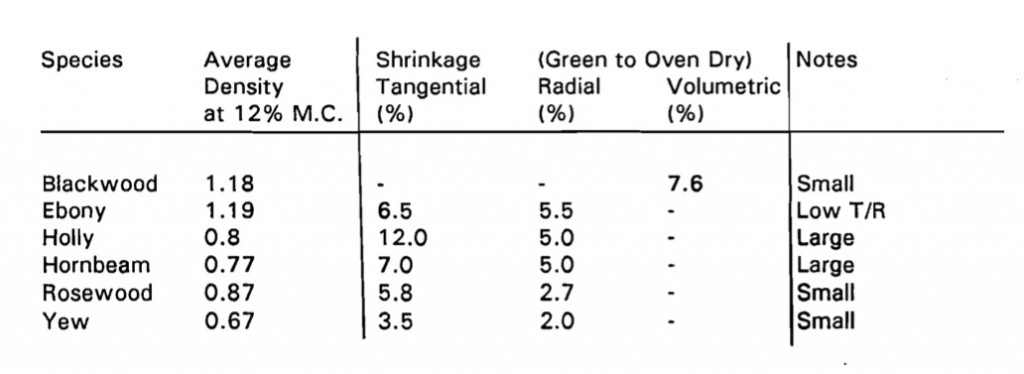

The first of the PHYSICAL properties is that of density. This can be loosely defined as the weight of a given volume of a substance in relation to the weight of the same volume of water. Thus, suppose that 1 cubic foot of a particular timber weighs 68-1/2 Ibs. and cubic foot of water weighs 62-1/2 Ibs. then by dividing 68-1/2 by 62-1/2 we obtain a density of 1.09 for the timber. Density is of major importance since it affects the resonance of a timber, and the densities of cocus wood, partridge wood, ebony, and African blackwood all fall within the range of 1.1 to 1.2 when the MOISTURE CONTENT of the timber is about 12%. I will speak of moisture content later. In comparison with these densities, those of the indigenous timbers used before cocus wood etc became available varied between 0.75 and 0.85. It is clear that the resonance of pipes made from the indigenous species must have been inferior in tone to those of today, since the density of blackwood, for example, is half as much again as that of the indigenous species.

A second physical property affecting musical quality is the STRUCTURE of the timber. For clarity and richness of tone a timber must have a FINE, as opposed to a COARSE, texture.

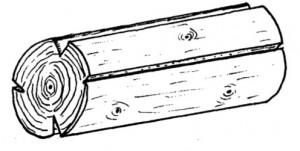

A third physical factor affecting musical quality is SHRINKAGE. As we know, all timber shrinks as it dries. Suppose we represent a log thus:

As it dries out the outer layers shrink on a core which remains wet and therefore the same size. Something must give, so the outer layer splits over the wetter core. It is of great advantage therefore to cut up the log as soon after felling as possible into sizes required and, in the case of blackwood this is now generally done. The ends are coated with wax to retard end-drying and related cracking.

————————————————————————————————-

1This article is based on a talk first given to the Piobaireachd Society Conference in Bridge of Allan, Scotland, in 1991 by the author and later at North Hero, Vermont, U.S.A., in 1992.

2David Moore is a retired tropical forester having served for many years in the U.K. Colonial Forest Service then for some twenty years as a Consultant to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

9

There is a great deal of mythology attached to timber seasoning but in point of fact effective seasoning is no more than controlled drying to a point where the remaining moisture is in equilibrium with the average relative humidity of the environment in which the timber is to be used.

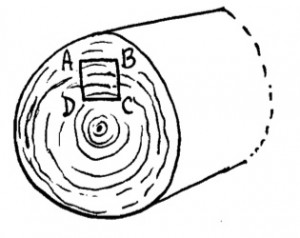

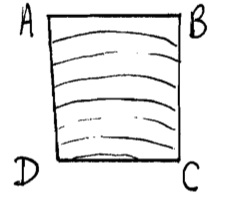

Considering shrinkage in more detail we suppose that the log shown below is being cut in the saw to provide as many chanter blanks as possible, the remainder going into shorter components such as drone sections.

The square ABCD represents a chanter blank and with respect to the growth rings, the face AB is a tangential face while the face BC is a radial face. Shrinkage on the tangential face can be up to twice that on the radial face so that when the chanter blank is properly seasoned it is no longer a square in section but oblong as:

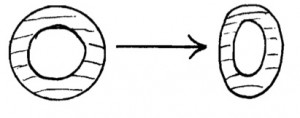

When a chanter is turned from a properly seasoned blank it will remain relatively stable but if the timber is wet when turned, not only will the outer surface of the chanter become in time slightly oval but more importantly the bore of the chanter will change from being perfectly round to becoming, in time, slightly oval as the timber dries out. The deformity is exaggerated in the figure for the purpose of illustration but in reality we know that a deformation of only a fraction of a millimeter will affect the acoustical properties of the instrument.

Now we shall consider a fourth physical factor, namely DIMENSIONAL STABILITY. Let us assume that we have a chanter made from fully seasoned timber. Over its useful lifetime the chanter will be exposed to widely different moisture conditions depending on the how wet a blower the player is and the humidity of the environments in which the instrument is played. Minute dimensional changes occur in response to such variable conditions. Any wood therefore in which tangential and radial shrinkages or expansion are approximately similar will retain the circularity of the bore to a greater extent than those in which radial and tangential shrinkage differ widely. The presence or absence of natural waterproofing agents in the wood will greatly increase dimensional stability and of course the example of such as wood par excellence is to be found in African blackwood (see Appendix II).

10

Earlier I said that timber characteristics can be divided into PHYSICAL and MISCELLANEOUS DEPOSITS. WATER is one of the miscellaneous components of all timbers. In some species such as balsa it can weigh, in freshly felled logs, more than ten times as much as the dry wood matter itself. In others such as blackwood it constitutes only about 25 to 30%. For many purposes it is necessary to accurately know how much moisture is contained in wood, for instance, kiln drying of boards or in the manufacture of plywoods, etc. This measure is known as the MOISTURE CONTENT and is expressed as a percentage of the weight of the dry wood matter present.

In practice the moisture content is frequently determined electrically by means of a resistance measurement but for accurate determinations a sample of timber is weighed then oven dried with weighings repeated at intervals of about a half-hour unit two successive identical weights are obtained thus indicating that all of the moisture has been driven out of the wood.

Investigations over many years show that timber settles down to a moisture content in equilibrium with the average environment at about 12% moisture content. It will be lower in wood stored in a centrally heated house and higher in wood kept in a damp cellar. In practice pipe makers keep a supply of timber blanks in their shops for a selected length of time at the end of which it is assumed that the timber is suitable for working.

The second of the MISCELLANEOUS DEPOSITS are those laid down in trees as the trunk and branches pass through the transition phase between the actively growing cambium just below the bark and the physiologically inert but mechanically supportive tissue of the heartwood. These deposits in this transition area which later become heartwood include silica, mineral oils, resins, and gums. Some of these agents provide waterproofing and improve the dimensional stability, as in blackwood. In the case of ebony the nature of the deposits are different. During the transition phase of tree growth ebony undergoes a process analogous to, but not identical with, fossilization.

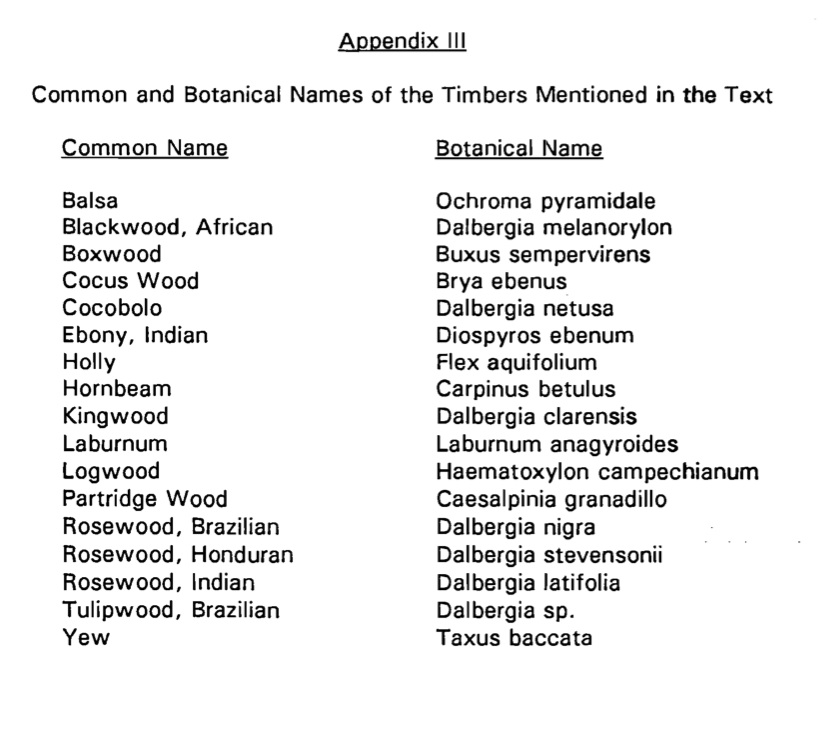

Having discussed the characteristics of timbers for pipe making we now turn our attention to the subject of AVAILABILITY which I propose to deal with in three chronological but overlapping periods: INDIGENOUS, TRANSITION, and EXOTIC. During the INDIGENOUS PERIOD bagpipes were made from local timbers only. This period spans the time from the 14th century to the late 17th century. We can only surmise at the species then used in pipe making but it seems probable that they used boxwood, hornbeam, laburnum, holly, yew, and various fruitwoods.

The TRANSITION PERIOD began in the 17th century and lasted, surprisingly, until the early years of the present century. During the 16th century the Spanish, English and French were engaged in bloody rivalry in the West Indies and by the first half of the 17th century the English were colonizing Barbados, St. Kitts, Trinidad, Jamaica and other places. It seems reasonable to suppose that for many years afterwards cargoes shipped to England from these colonies consisted of valuable commodities such as tobacco and spices. At a later time, perhaps during the late 17th century, additional resources such as fine timbers and logwood for dyes began to be exported. In the case of woods for pipe making, these colonial timbers would have become available by the end of the 17th century and would have included cocus wood from Jamaica, lignum vitae from various places in the West Indies, and later, rosewood from Belize, followed by partridge wood from Venezuela (see Appendix III for botanical names).

Parallel to but later than developments in the West Indies, the fledgling East India Company was laying the foundations for what would eventually become the “Jewel in the Crown” of the then British Empire,… the colonial annexation of India. From the early 1800’s onward, gradually increasing shipments of ebony and rosewood from India

11

together with exotic timbers from the West Indies progressively displaced the indigenous timbers previously used to make bagpipes. Details of wood purchases by the Glens of Edinburgh in the mid 19th century can be found in Hugh Cheape’s excellent paper “The Making of Bagpipes in Scotland”3. The same paper also records the fact that as late as the early 1900’s a pipe maker in Dundee was still making pipes from laburnum and that Robert Reid, whose shop I remember in George Street in Glasgow, remarked of the pipes “they are all right for lighting the fire with!!” Certainly I know of one laburnum set being played in the late 1920’s to early 1930’s in the Boys brigade Band in which I was a piper.

I consider the time from the early years of this century to the present to be the EXOTIC period since nearly all Highland pipes made in this time have been made from imported timbers. Early this century, as cocus wood became more scarce (and remember there was great competition for supplies from such manufacturers as Boosey and Hawkes for other woodwind instruments), ample supplies of ebony met the demands. Concurrently, and particularly after World War I ended and the United Kingdom took over German East Africa (Tanzania) the region was opened up to increased commerce. Blackwood came on to the market in steadily increasing quantities and, because of its superior characteristics, has in time displaced ebony. I would imagine that from about 1945 all reputable pipe makers have used blackwood exclusively.

It is worth discussing this species in more detail. The distribution runs from the old Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, through Uganda and Kenya to Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique and the two Rhodesias. It grows sparsely throughout the savanna type of forests called miombo forests which occur at elevations of less than 5000 feet in rainfall zones of 35″ to 45″ per year and with dry seasons of 7 to 8 months. Soils are generally poor and the total of all tree crowns in the forest cover less than 50% of the ground. Botanically, blackwood belongs to that wonderful genus Dalbergia which with over 120 species includes such important “musical” timbers as kingwood, Brazilian tulipwood and rosewood, cocobolo, Honduras rosewood, and Indian rosewood. The tree is often a scruffy, multi-stemmed runt of 15 to 25 feet but occasionally up to 50 feet with a short trunk up to 12″ in diameter. The species has been heavily exploited commercially but to put this in perspective I understand that bagpipe manufacture accounts for about 2% of the volume exported. Much of the miombo forest is being destroyed by shifting cultivation and by excessive burning to stimulate new wet season grasslands for grazing. Regeneration is therefore at a standstill and since it can take up to 80 years for a sapling to reach commercial size the outlook for long-term supply is poor indeed. Actual quantities reaching the United Kingdom have improved in the past years but this is because export in Tanzania is no longer restricted to one government agency. Private companies are now exporting, but this means that the existing crop will be cut out all the sooner.

The question arises, “from what will bagpipes be made when traditional materials become so scarce that timber is priced out of the market?” Various types of plastic have been available for many years but the tonal qualities are generally unacceptable. In the case of maple (Acer. sp.) impregnated with epoxy resin the density is in the region of 1.18 and the tone is excellent but, particularly in the case of Highland pipers, there are objections to the cream colour of the wood. Hamish Moore has produced quite a number of sets of smallpipes from an industrial material called Permali which is used mainly as a high-voltage insulating material. Permali consists of laminates of beech (Fagus sp.) impregnated with high density resin which is then heat treated and produces a material of a pleasing reddish/brown colour which, when turned on the lathe, appears to have a natural and interesting grain. The material is virtually impervious to moisture and therefore

——————————————————————————————————–

3″The Making of Bagpipes in Scotland” by Hugh Cheape M.A., B.A., F.S.A. (Scot.), pages 596 615, From the Stone Age to the Forty Five, published by John Donald. Edinburgh. 1983.

12

to dimensional change, the density is 1.28 (c.f. Appendix II) and the tonal quality excellent. It is certainly the best of the substitute materials by far and, for those areas in which extremes of relative humidity occur, it is ideally suited. This is especially so for small pipes~ in the manufacture of which technical difficulties are encountered which do not arise in the machining of Highland pipes.

Appendix I

Characteristics and Availability of Suitable Timber Species In Relation to the Past, Present, and Future Manufacture of Several Forms of Scottish Bagpipes

13

Appendix II

Available Information Concerning Density and Shrinkage During Drying of Several Timbers which have been, or are used in Bagpipe Manufacture (Personal communication from Dr. J.D. Brazier, B.Sc., D.Sc., F.I.W.Sc.)

14

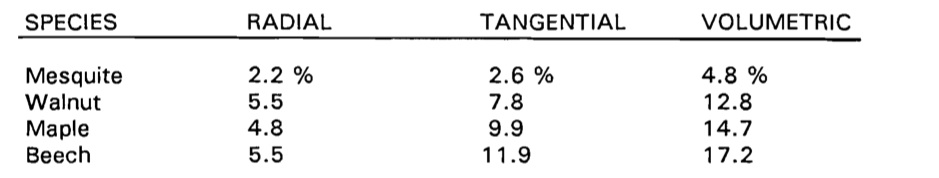

American Wood for American Made Bagpipes

When Mike Dow, pipemaker, carver and cabinet maker from Maine sent in his ad copy, he included the following page of information about that Texan spice wood called mesquite. The editor recalls talking with John Liestmann, a Northumbrian pipe player from Texas who had built a set of Northumbrian smallpipes from this wood.

The American honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) is one of the hardiest trees that grows in the harsh southwestern United States climate. It can be found from the Gulf of Mexico in southern Texas to Death Valley, California, the hottest place in the western hemisphere.

All wood loses and gains moisture trying to accommodate itself to the ever changing ambient relative humidity. Mesquite has two very important qualities that are connected to this fact:

1) Mesquite shrinks and swells very little when it loses or gains moisture, resulting in negligible volumetric shrinkage.

2) Mesquite shrinks and swells almost equally in both its radial and tangential directions. The values for mesquite are compared with those for other familiar woods in the table below for wet, green (live) condition to a dry climate.

Mesquite’s low and nearly identical radial and tangential percentages and low volumetric number indicate that it has an extremely high level of dimensional stability. This is good news to the person who owns a set of bagpipes made out of this wood. When that instrument gets put through the North American torture of cold dry winters followed by hot humid summers, its inside bores and outside diameters will stay cylindrical. Bagpipes made out of other woods will gradually deform into a cross-sectional shape that is more oval. This is because one dimension is changing more than the other (see David Moore’s article for more details).

Another of mesquite’s qualities is its hardness. It has more than twice the surface hardness of red oak, and nearly twice that of hard maple. Quantitatively, that means that it takes 2340 Ibs to push half the diameter of a 7/16″ steel ball into a piece of mesquite. The force needed for red oak is 1060 Ibs, while that for hard maple is 1450 lbs.

Mesquite is a handsome wood with striking grain patterns and, like cherry and boxwood, is light sensitive, which means that as it ages it darkens. It changes from the lighter reddish tan of newly cut wood to the richer reds and browns. Its inherent beauty and stability make it a wood well suited for the Scottish smallpipes.

15

A BORDERLINE (PIPE) CASE by Alan Jones

Am I really admitting to being oe’r the border yet another time! In fact, since I last wrote the article that was published in JOURNAL No.5, I have actually made two further visits to the land of the lowland and border bagpipe – and both of these subsequent trips within the last three months.

Last October, my whole collection of bagpipes was sent (“air mail”) to Scotland, for a two month exhibition at historic Old Gala House, Galashiels a wonderful building dating from the 18th century and earlier, that has now been converted into a museum.

Thanks to the efforts of Gordon Mooney and the Scottish Traditional Music Trust, arrangements were negotiated with Etterick and Lauderdale District Council to put my pipe collection on exhibition as part of the Scottish Borders Festival and Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society “Gala Rant”.

Each of the last three years, the L.B.P.S. has organized this event (generically referred to as the “Collogue”) firstly in Jedburgh in 1991, Peebles in 1992, and Galashiels in 1993; all border towns with strong historical connections with border piping.

The history of the border bagpipe tradition can be traced back to the 12th century. Evidence of a stone water spout in the form of a pig playing a bagpipe can be found from this peroid at Melrose Abbey. As is common with other border abbey’s, the Melrose order encouraged the work of musicians, and early evidence supports the theory that pipes were in use at least from that time onwards. A similar carving can be seen in Roslin Chapel, but the Melrose Abbey

16

bagpipe . connection pre-dates the more northerly religious establishment.

Pipers were employed throughout the border boroughs or “burghs” dating from the 1400’s, whereby they would normally play before sunrise to signal the dawning of the (work) day, and in the evening, to indicate the night curfew. Often, the old form of County Councils paid these men a small sum of money for their services and into the bargain (generously?) provided a pair of shoes! For such a seemingly meagre reward, pipers, in addition to their regular daily duties, had to play at official functions and ceremonies as and when required, and in the most part, were required to turn out dressed in a military style uniform. Amongst others, several generations of pipers belonging to the Hastie family continuosly worked in Jedburgh, there were the famous Anderson’s of Kelso, as featured in the much loved song and Burn’s poem “John Anderson my Joe,” the Jaffrey’s of Hawick, and one very famous piper by name of Geordie Sime, personal piper to the Duke of Buccleuch during the 18th century; all of whom faithfully upheld the then noble tradition of piping in the borders. Geordie Sime was based at Dalkeith, and it is noted that he was the best piper of his time and wore a yellow coat, red breeches, and a blue bonnet.

Getting back to more modern times, the Galashiels exhibition, and the 1993 border bagpipe connection, there was certainly quite a story to actually getting the pipes prepared and shipped from Canada to Great Britain. Much categorizing, itemizing, packing away in their respective boxes, plus transporting to the city (Montreal) for crating took place before shipping paperwork, customs and insurance documents and other details could be finalized to get them onto an aircraft. Not a simple task by any means with around 80 sets involved.

The pipes were delayed on leaving Canada, and then on reaching Glasgow (via London), got entangled in customs paperwork and the bureaucracy of import duties.

Fortunately, Etterick and Lauderdale District Council and staff at the museum, became actively involved with T.V. and extensive newspaper coverage (e.g. in the national Scotsman, local Selkirk Advertiser, Border Telegraph, Borders Gazette and Southern Reporter etc.) . . “Bagpipes destined for museum exhibition get held up by customs”. seems to have been the press required to conclude “all’s well that ends well;” the pipes eventually arriving in Galashiels two days before the commencement of the opening of the exhibition. Phew, close! Two frantic days of further activity by Mr. Mooney and museum staff saw the pipes dutifully displayed in cases, and relevant texts, history and photographs going together to complement and complete a very impressive exhibit indeed.

Due to unforeseen circumstances, my girlfriend Patricia Johnston – (whose border Scots ancestral claim to fame, is that they were involved in one of the longest and bloodiest of all clan feuds with the Maxwells) – and I, could not leave until Friday the 15th of October. We flew from Montreal to London, with a connecting flight to Glasgow; arriving there to pick up a hire car and drive down to Galashiels for the L.B.P.S. Gala Rant.

It proved to be a glorious day to be driving through the

17

Scottish borders. Beautiful countryside along both the highways and byways that we traveled, over hill and dale, past craggy peaks and high mountains, forests and farmlands, until we eventually got to Galashiels a couple of hours later.

When we actually arrived, it was mid afternoon and the Gala Rant was in full swing; Joan Flett (co-author of a definitive work on Scottish folk dancing) having just finished her lecture on the folk dances and dancing traditions in the Scottish border country. Great to make acquaintance with friends both old and new – Jon Swayne, Hamish Moore, Colin Ross, Gordon Mooney, Julian Goodacre, Matt Seattle, Jim Gilchrist, Freddie Ord, Robbie Greensit and Ann Sessoms to name but a few and many of whom have been instrumental in, and an integral part of, the lowland pipe revival of the 1980’s and 90’s.

Colin Ross was next to present a very humourous, enlightening, and well informed lecture/demonstration on “playing for dancing;” utilizing the fiddle for the musical demonstrations. Following Colin’s talk, Professor Andy Hunter got up and expressed his concerns that there were too many non-Scottish influences enacting on the L.B.P.S., and that it was loosing it’s Scottishness. A fairly heated debate took place: the outcome of which was that it was decided that issues would be better and further discussed at the L.B.P.S. AGM rather than at the Gala Rant.

At this point Patricia and I adjourned to go upstairs to look at the exhibition. It was certainly immediately apparent on viewing the pipes, that Gordon (Mooney) and Shona Sinclair (assistant curator) had done a magnificent job of setting everything up.

An informal discussion and viewing took place, during which time, many questions about my exploits were answered. A very vibrant and amicable atmosphere prevailed, and for me, it was just great to be surrounded by both my pipe collection and all the enthusiasts and piping personalities. The pipes and historical texts thus displayed looked magnificent, and were certainly beautifully augmented by prints, illustrations and music in the appropriate setting of Old Gala House. Further to much subsequent chat and mingling, good positive feedback on the quality of the exhibition was received from many of those persons present. Unfortunately, due to limitations of display cases, it was not possible to exhibit all of the instruments at this time.

A little later on, one could find, in all the various nooks and crannies throughout the building, all manner of different pipes being played, from the border and Scottish smallpipes, to the Cabrette and Hungarian Duda.

Further to much chat and discussion, there was a call to go to the kitchen for shortbread and tea, prior to concluding the afternoons activities and moving over to the drill hall down the road to attend the evening concert.

Derek Robeson, along with Gordon, had done a fine job of promoting the exhibition through local and national newspapers, plus radio and television. Special thanks also go to Ian Brown (of Etterick and Lauderdale District Council) who was most receptive and helpful in negotiating successfully the go ahead for the exhibition. Of particular note was an extremely humourous and entertaining Border’s Television news feature that Gordon did, in

18

playing various bagpipes (e.g. Bechonnet, Gaida, ++) from the collection whilst his two children danced as he played. The Hungarian group Vasmalom, playing modern arrangements of traditional tunes and featuring the wonderful Duda (Hungarian bagpipe) playing of Balazs Szokolay, gave a very fine performance, along with Hamish Moore playing Highland and Lowland pipes, and Dick Lee on saxophone, giving us a very polished. and eclectic repertoire. Quite an avante garde feel to the music thus far played this evening. Others to perform were Ray Sloan (Northumbrian pipes) and Lynn on guitar and vocals, Moebius – Jon Swayne, Judy Rockcliff, Don Ward, all playing Jon Swayne border pipes – Matt Seattle on fiddle, plus other local musicians. Certainly a very interesting evening of music, though not too well attended. Possibly either – the fact that the temperatures (both inside and out!) being a little on the cooler side, or the somewhat non traditional eclectic mix of music thus presented – might have had a bearing on the lower attendance figures for this particular event.

By 3 a.m., and not having slept for two days, Patricia and I were very pleased to partake of a well earn’t good nights rest.

Sunday October the 17th-

On returning to Old Gala House, Ann Brown of BBC radio Scotland carne in to interview me. A very lively interview ensued, with many well informed questions asked. Discussed with both Gordon Mooney and myself were the long term plans to promote the establishment of a centre for Scottish traditional music under the auspices of the Scottish Traditional Music Trust, and also the potential for setting up a permanent bagpipe museum/exhibit at Old Gala House; negotiations on these issues being currently underway.

Following the interview and having then given an introduction on the subject of “the insane art of collecting bagpipes,” I gave a guided tour of the pipes to an enthusiastic group of listeners, answered questions, and took out different sets from their cases to demonstrate the various tonal qualities of individual instruments. A very relaxed and enjoyable afternoon was had by all.

An observation that I must comment on, is the fact that it was such a luxury to be able to take pipes out of their cases, tune up the drones, and low and behold, THEY PLAYED FIRST TIME! Definitely a happier family of pipes in the more bagpipe conducive climate of the British Isles (than in Canada and the North Eastern US). I must conclude from personal experience, that if a bagpipe is PLAYED in the environment in which it is made, then it certainly gives less trouble to its owner than if it “emigrates.”

On the Monday, Gordon (Mooney) and I met Ian Brown (of Etterick and Lauderdale District Council) for lunch, to discuss future plans for the second bagpipe exhibition to be set up for 94, and also the curriculum for various educational courses and workshops. Very positive feedback from Ian, and we agreed to go ahead to bring these plans to fruition.

Beautiful weather was with us as we walked back to Old Gala House – enthusiastically discussing future plans and potential.

I spent the afternoon working on the collection with Shona, re-arranging, and better placing the pipes in their cases.

19

Gordon and Barbara gave Patricia and I some great hospitality, along with many jokes and stories, and pipeopheliacs Jones (pipecase 1) and Mooney (pipecase 2) participated in the customary ritual of exchanging piping news from both sides of the Atlantic.

The next couple of days I further spent working on cleaning and servicing the pipes at the museum, and also traveling around the region with Patricia. We checked out the Scottish wares produced by the local woolen mills in Hawick, and also got to see and photograph some of the old border/pastoral pipes in the Hawick museum.

Wednesday the 20th – Pat, A.J.,and G.M. ventured 70 miles south to Morpeth “en Angleterre” to attend the Nothumbrian smallpipers get together in the Black Bull pub. About 15 pipers in all, with a general play around led by Colin Ross, Jim Hall, and Pauline Cato. Great music and atmosphere. Met up with Freddie Ord the pipe maker again, who had made a copy of the Jamie Allan set of Pastoral pipes in the Morpeth Chantry bagpipe museum. I was about to add this set to my collection later that week. This most enjoyable evening was rounded off with a fine gourmet meal of North Sea cod and chips. Back across the border we go – tired but inspired. As a matter of fact, we almost imagined ourselves the equivalent of a modern raiding party of Border Reivers; only this time, the spoils were Northumbrian tunes!

During the evening of the 22nd we visited Julian Goodacre and his wife Sharon (who is from Minnesota) in the town of Peebles. Enjoyed a good meal and visited his new workshop to see some of the latest creations. His current project was constructing a loud border pipe in A.

Saturday the 23rd of October-

Patricia and I left to move further south on our travels – stopping off to have a wonderful afternoon tea with Lance Robson, whose hospitality to wandering minstrels is not to be missed at any price, then going over to Annie Snaith’s house in Elsdon – way out on the Northumbrian moors. Each month pipers meet at the house of piano player, Annie’s. She is now in her 80’s and used to play frequently with Billy Pigg, and pipers have in recent times, started going to her house again. A meeting takes place there one Saturday a month. This appears a fine way to encourage the continuing tradition of playing pipes and traditional music in the rural homes of Northumberland; just as Forster Charlton used to explain to me when he would visit Billy Pigg’s house for wonderful evenings of music and conversation.

Although I often record music when I travel, on this occasion, just a few photographs were the order of the evening. Lovely music and a welcome tea and scones were eaten to complement a fine musical gathering in front of a wonderful fully stoked up living room coal fire.

That night, Patricia and I were staying with Colin and Ray (Ross) in Whitley Bay. We set off into the frosty night for the 40 or so mile journey to the coast, over windy hilly roads, often with thick foggy patches in the valley sections when visibility would be but a few feet. It must have been at least 2.30 a.m. before we took rest from our travels . . . . Another day dawns . . . . and next morning the 24th, Pat and Ray went off shopping whilst Colin and I got down to the business

20

of reedlng up Freddie’s pastoral pipe with reeds sent over by Sam Grier from the U.S. Following some finishing work by Colin, a beautiful set of pipes with much potential was now set up with chanter reed (working at this time for an octave and two notes) regulator reed and the two drone reeds. I couldn’t resist asking Colin what he might have for sale. I pulled down a lovely B flat Scottish smallpipe chanter off the shelf – and couldn’t resist a purchase. A superb sounding chanter that I was very happy to add to the collection. I reiterated my interest in getting the 17 keyed ivory and silver chanter that we had discussed, along with confirmation of what I had on order (more border pipes and Northumbrian pipes etc.) For me, a visit to Colin’s house is like discovering heaven (on earth!) surrounded by fine bagpipes along with much good conversation and stories on piping lore and personalities. History in the making!

Next day (23.10.93) saw us on the road once more – taking the coastal route up through Alnwick and Berwick to visit Edinburgh. A very pleasant trip and visit over “des nouvelles routes” with fine weather to help us on our way.

That evening, we returned to stay once more at the Mooney house in Newstead. Yet another great evening of stories and conversation.

The 26th saw me back at Old Gala House for a second interview with Ian MacInnes of the BBC Radio Scotland “Pipeline” programme to be subsequently broadcast at a future date. I was suffering from a very bad sore throat, so was not in the best of health at this time. However, certain things must get done when they have to be done. . . . I was also pleased to met up with Bill Lindsay, an old colleague of mine whom I hadn’t seen for 20 years. Back south that afternoon to visit with Ray Sloan in Northumberland. We got lost after Otterburn and arrived very late that evening at Ray’s. A drink and a good meal helped to reduce the adrenaline level, and we settled in for an evening of song, piping and good chat; staying over that night. Before leaving “piping country,” we called in at Robbie Greensit’s and Colin Ross’ in Whitley Bay and then away on the M1 south to get to Wales – the beautiful land of mountains, castles and abbeys, song and triple harps.

The Sequel-

In conclusion, I’ll briefly tell you about the “follow up” second trip to the borders in January 94 to put the pipe collection away.

I flew to London Wednesday the 19th, stopped over there for two days, then flew to Newcastle where I was met by Ray (Fisher) Ross on the 21st to stay over yet another time at the Ross residence.

As always, great chat with Ray and Colin, plus much time spent viewing Colin’s array of chanters and pipes in his pipe room. Saturday morning Ray and I went shopping to search out a fringe, to cater to the Jones eccentricity of a fringe decorated wine red velvet bagcover. Having only found white, Ray offered to dye the fringe red. Such a brave soul, being so helpful in giving the customer exactly what he wants. Purchases made, back to Denebank to

21

mix the required brew. In the afternoon, whilst Ray worked on the cover, Colin and I set to working a little more on the Freddie Ord pastoral set to refine the reeds to try to get them to play over a greater range. Also, much interesting pipeology was furthermore discussed to conclude an industrious and, as always, interesting day. To add a “footnote” to the cover story (i.e. cover, as in velvet), Ray also managed to modify two covers that she had made for me a year earlier, which had inadvertently had their fringes mixed up. We are still trying to fathom out why the white fringe ended up with the black bagpipe and the black fringe with the white bagpipe. Yes, life is really tough at times; however, all’s well that ends well .. ., and I now rest peacefully in my bed!

Sunday the 22nd saw more work on reeds and chanters, checking pitch and intonation, plus trying new chanters and reeds “off the shelf,” and also my recording an informal interview with Colin. Great ambience and spirit as always, and it was concluded by my buying one of Colin’s fine Northumbrian pipe chanter reeds. With my now elegantly dressed pastoral pipe . . how time flies when you’re enjoying yourself . . five o’clock came around pretty quickly; at which time Richard Butler picked me up for us to go for a meal and to take me to meet Lance Robson in Hexham. Good food and fine company, fascinating conversation and much catching up to do on news and stories, before rendevousing with Lance at 8 p.m. right on time as usual and certainly the envy of anyone who needs a lesson in punctuality. Another great evening spent on old piping lore, personalities and music.

Monday saw us off to the Morpeth Chantry bagpipe museum, and as always, great to view the pipes thus displayed there. I informed Ann Moore of her interview and broadcast that I had recently heard on CBC (Canadian) radio just a couple of weeks before. This particular broadcast instigated dozens of listener phone calls, to rectify both the condescending attitude to the humble, inoffensive and dearly loved by so many – little bagpipe – and the announcement that Northumberland was in Scotland! (Could this have been a heathen plot to try to change the course of history?)

Next stop was Longframlington to visit Dave Burleigh’s workshop, where I could not resist but make an offer on a wonderful “Capitain” Breton Biniou Koz that had been hung up in David’s workshop for probably 20 years or so! I also managed a rare photo of David (with Lance) in his workshop. On up the Coquet valley to Joe and Hanna Hutton’s in Rothbury, with whom I always enjoy a visit and where I’m always made to feel so welcome. Great to see them again. I was extremely pleased to record an interview with Joe and Lance much interactive conversation about pipes, piping personalities, friends and acquaintances, along with many fascinating historical facts and details. Evening approaches time to leave and get back to Hartburn in time for Lance’s NSP class.

Sarah Graham, Alisa and Francis Dungait, along with Corina Hall – all playing David Burleigh pipes. I was honoured to be lent Lance’s latest set of pipes – a superb 17 keyed ivory and silver set made by David also. A very structured and useful lesson, and good to participate and do some sight reading. Lance played his circa 1800s Robert Reid ivory and silver set – always such a

22

pleasure to see and hear what is probably one of the finest sets of Northumbrian smallpipes ever made, and later that evening, we jointly delved into the wonderful archives of piping lore that he has in his magnificent historical collections; going on way into the wee hours. Much tea and conversation later, and just before retiring to bed, Lance told me a wonderful Joke: “What is the difference between Northumbrian smallpipes and Highland pipes? Well, on the Northumbrian smallpipes, you play one clear note at a time, whereas on the Highland pipes, you have to play half a dozen notes before you find the right one!” Next morning, Lance took me to Morpeth so that (yes, you’ve guessed it), I could once again visit the bagpipe museum. Quite a regular there these days! Having more hours to spare for this particular sojourn, I spent much time going over the pipes in detail, chatting with Ann Sessoms, and listening to the recordings of the pipes whilst viewing them. Some photographs later . : . . ,

I took a bus, then a long cool and rather wet walk, to arrive at Robbie Greensit’s house just after lunch. We discussed various piping matters, including the possibility of my getting a set of regulators on one of my sets of Scottish smallpipes. Robbie has developed some wonderful B flat regulators to go with his B flat sets of pipes. Following my visit with him, I walked down the road and across the railway track to once more, call at the Ross house. Here I re-looked at the E (only the second he has made) and D NSP chanters, plus a Scots smallpipe chanter in holly wood to match my border pipe holly wood drones that Colin had made. I decided to take Colin up on his offer of bringing this chanter back to Canada with me to try it in my border pipes. After about two hours, Lance arrived to whisk me away once more – (Freddie Ord) Pastoral pipes et al – as collected from Colin. Next day Lance was his usual ace border guide that he is, taking me firstly back to Dave Burleigh’s to collect the Capitain Biniou, and then on to Gordon Mooney’s north of the border. Wild erie beauty as we drove on the A68 past where the battle of Otterburn took place, past Catcleugh (pronounced “Catcluff”) reservoir, at a point where one can see Kielder forest beginning away in the distance. There was mist and snow on the hills~low clouds – faded greens and browns on the landscape, and much high wind at Carter Bar. Lance pointed out the “stels” for the mountain sheep to shelter in during the winter, whereby hay is kept for them to eat during times of inclement winter weather. Once over the top, and with Scotland magnificently spread out before us, we were making our descent down into Jedburgh, where we stopped for lunch. The vistas were, as always, breathtaking over southern Scotland, with a little snow on the upper elevations of the Cheviots; this mountain range stretching over both sides of the border, flanked by Roxburghshire on the north and Northumberland on the southern elevations. The evocative landscape caused my mind to return a couple of hundred years and for me to try to imagine what it must have really been like in the days of the border reiving. A very hard existance indeed, I’m sure.

Whilst at Jedburgh, we viewed all the things tartan and Scottish: subsequently arriving at Mooney’s Melrose music shop by mid afternoon. Lance rushed off to be back at Hartburn to give

23

further piping classes, and I remained to enjoy one more great piping evening in Newstead.

On Thursday the 27th I worked a hard twelve hour day photographing my pipes at Old Gala House, cleaning and oiling them and putting them away in their respective boxes etc. During the evening, Gordon and I met up with professor Freddie Freeman who is actively involved in the promotion of the Scottish traditions and is also a director of the Scottish Traditional Music Trust. A fascinating evening was spent discussing culture, music, and language. Interesting to be informed of the fact that Welsh (a Celtic language) was once spoken in the Scottish border country. In this respect, on learning about the history of the Johnston clan, I read of a very interesting point that has a very personal connection for both myself and Patricia – i.e. the first mention of the name Johnston, was in the form of “Jonstun” (John’s farm), or “Jonestun!” (Maybe we WERE connected in a former life!).

Friday the 28th – following more museum work, photographing etc., going to meet the Borders Enterprise people, and having lunch with Ian Brown, Shona, Gordon, and Freddie, to discuss future activities/Scottish Traditional Music Trust affairs, I concluded my museum work late that evening after a second twelve hour day. Murphy’s law prevailed, and much to my embarrassment, I managed to set off the museum alarm system just before leaving …… ! At least I know that the pipes are well taken care of!

Saturday the 29th of January 94 –

I viewed many Highland pipes in the shop of Mr. Mooney, tried a number of them, took photographs and bought recordings and books. That wonderful Northumbrian by the name of Mr. Lancelot Robson, right on time as always, came all the way back to Melrose to collect me and immediately take me south to Newcastle airport – 65 + miles – to pick up my hire car. As we parted, I reminded him of some wonderful words that he had said to me that I have never forgotten, and that greatly help me on my

“To pipers’ there are no strangers, just friends that haven’t met.”

Alan Jones – March 1994

24

| , |   |

25

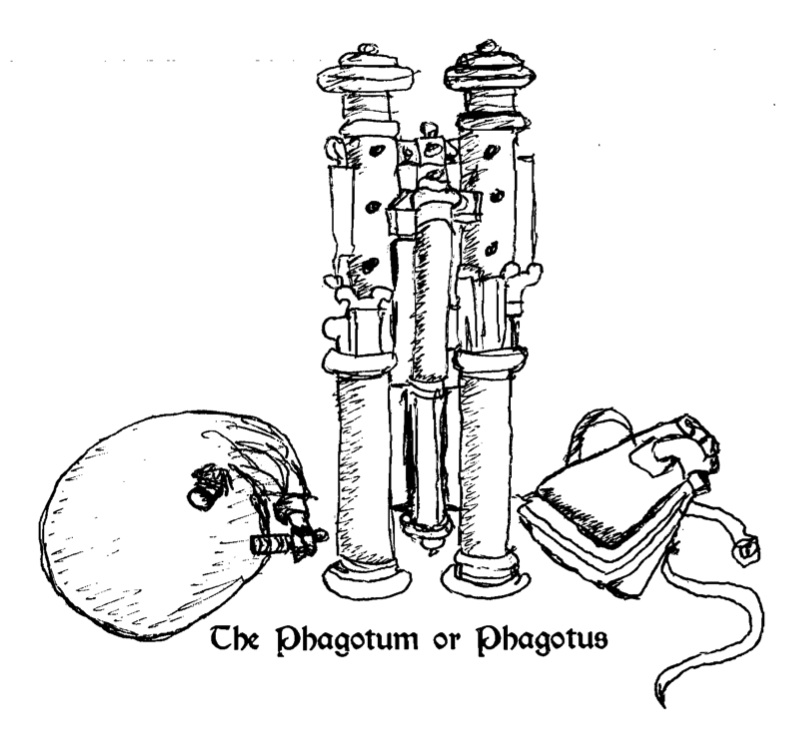

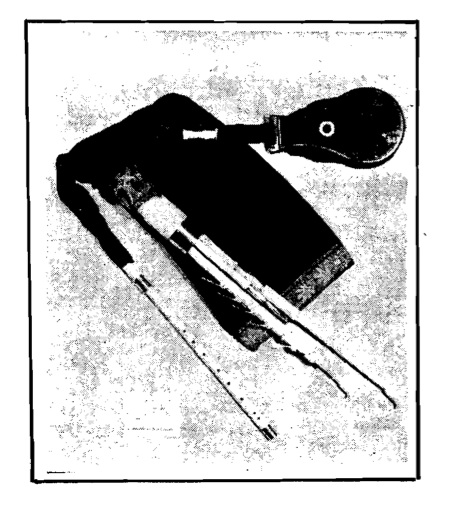

The Phagotum and William Cocks by Eoghan Craig Ballard

In the early years of the sixteenth century, Afranio, the Canon of Ferrara, constructed a complex bellows blown bagpipe for use in religious music. There is scant information available concerning this instrument. It was called the Phagotum or Phagotus. The only contemporary description of this bagpipe was provided by the makers’ nephew, one Ambrogio Albanese. Ambrogio, in 1539 published his description with illustrations. Another manuscript dated 1565, according to William A. Cocks 1959 article in The Galpin Society Journal, gave the scale and fingering for the Phagotum.

The Phagotum is a strange side bar in the history of bellows blown bagpipes. It would have remained uncommented upon were it not for the indefatigable William Cocks. Mr. Cocks was fond of investigating historical instruments and recreated many including several extinct forms of bagpipes. His efforts have benefited Ethnomusicology in general and those interested in piping most particularly. Many people would take note of such an unusual instrument as the Phagotum, and if interested, collect the historic documentation. Perhaps they would go so far as to determine that no specimens are known to survive.

His curiosity not being satisfied by such research, William Cocks decided that he would attempt a reconstruction of the instrument from the various sources of information available to him. The article in The Galpin Society Journal chronicling his reconstruction of the Phagotum represents rare documentation of the process of solving an organological puzzle. It has much to offer anyone interested in the recreation of historic instruments.

Documentation on this instrument was very sparse. Certainly, it was insufficient to allow an accurate reproduction by an interested amateur of average skills. William Cocks was interested in tackling the problems posed by such a challenge. Who would not be daunted by the problems presented by an instrument bore that was something between 13.3 and 22 inches? Searching through contemporary records and the work of modem musicologists, Cocks determined that the instrument would have been tuned one whole tone above modem pitch in accordance with sixteenth century church practices.

Working in sycamore, Cocks plotted out the hole spacing using both the original illustrations as guides and the constraints of comfortable hand positioning. The instrument had a bore that, like the Rackett and the shuttle drone of the Musette de Coeur folded back on itself allowing a much shorter length of wood to be utilized in its construction than would otherwise have been the case. Through trial and error Cocks leads his reader through a practical and scientific resolution of some difficult construction and acoustical problems.

One of the results shared with the reader was the limits of his initial success. With so little solid information to work with, he modestly stated that his instrument was awkward to play. No further information has come to my attention indicating whether he attempted the improved reproductions of which he spoke. Perhaps the most interesting intimation he makes is that he had no interest in this instrument for its own sake. He felt that the Phagotum, even if reproduced with total accuracy would be only of academic interest. For William Cocks, the prize was in cracking the puzzle, in resolving the issues of measurement and acoustics. In documenting his process so honestly and accurately, Cocks offers valuable insights on reconstructing an instrument and an invaluable model of scholarship.

26

27

REGARDING THE STANDARDIZATION OF UILLEANN PIPES by Bruce Childress

(This article is an expounding on the open letter written on 8-27-93 by Patrick Sky.)

Standardization has has been the thought of many makers of the Uilleann Pipes. Especially the players who, for one reason or another, have decried the fact that once acquired, a chanter for the Uilleann Pipes is, more or less, unchangeable. Unfortunately, (or fortunately, depending on how you view it) any appreciable change in a chanter’s dimensions is likely brought about by an extreme change in weather conditions such as a flight from Anchorage to New Deli on a presently theoretical sub-space aircraft. That doesn’t say much for a typical reed now, does it? (a trip from a forced air home heating system to a smoky humid pub, for instance, in a sub-atmospheric Nissan Stanza) This is”a good time to think of what would be required to standardize the instrument we love in this time where all indications would seem to suggest that the Uilleann Pipes are gaining popularity such as they have never known.

A comparative study of the Uilleann Pipes construction with that of other instruments would be a good first step, and would serve to gain a little bearing on where the situation stands. What comes to mind for me is two other instruments in which I have had extensive dealings. The Hammered Dulcimer and the Acoustic Steel String Guitar. Note that these are two fairly popular instruments. Catching the drift so far? It would seem that a higher degree of standardization is commensurate with whether it is economically feasible to mass produce an instrument.

The late 70’s brought about a time when the Hammered Dulcimer was regaining popularity, after a time that it almost died out in attics and parlors around the world. (Although it has always been Iran’s National Instrument) After much hand-wringing back and forth between players and makers, and the trying-not-to-let-the other-guy-see-your-hand-wringing going on between makers, no one could really agree on what was best to produce a clear and ringing tone that didn’t resonate too much. Well, despite it all, Dulcimers sold and sold until someone had to divide the duties of Hammered Dulcimer making into “you do the bridges, you put on strings ….. ” etc. Thus present day small factories were born and the instrument became touched by many hands.

But, Hammered Dulcimer Players, don’t kick back in utter euphoria yet. Sure you can get a decent sounding dulcimer at a good price, but even as it would be taking your chances with an individual maker that you possibly don’t know very well, an occasional dog slips out despite the level of standardization. (I say “level” because nothing is truly completely standardized. More on that later.) A reputable individual maker would chivalrously

28

eat any lemons he cranks out, but once again you don’t know and you take a slight chance. So either way there is a small possibility of defect.

Which brings us to a lighter point. In light of high scale production tied in with some degree of standardization, Individual craftsmen are weeded out to the very best makers, because they can, then, concentrate on the very fine instruments, leaving the less expensive pretty good instruments to the factories. I have lesser models of pipes and various levels of construction to suit the prospective piper as I’m sure just about every other maker has. But I still become very enthusiastic over the one year projects that make the usual seem worth the while. This has happened both with the Guitar and the Hammered Dulcimer. The efforts of individual makers are almost always the cream of the instrument worlds crop. which isn’t to say that a company of makers couldn’t put out a highly professional quality instrument (C.F. Martin for instance).

Now let’s look at the degree of standardization that these examples of instrument are making, as well as the Uilleann Pipes. Take the Guitar. You have your choice of ‘X’ or ‘fan’ bracing. The scale length can vary from about 24″ to 36″ and still maintain the same tuning. Take the hammered dulcimer. Two instruments in the same register may be supported directly under the soundboard by what amounts to a log, or it can be a delicate miniature equivalent of a suspension bridge. Take (I almost forgot! The ultimate subject of this essay) the Uilleann Pipes. We have seen overall chanter lengths for the concert ‘D’ pitch pipes anywhere from 13 1/2″ to 14 1/2 “. Bores have ranged from a slow narrow taper to a wide flare. Some bores require a “rush” or anything up the bore to flatten it. I’ve Actually had to ream some out further. Hole sizes? Some require tape and filling others require undercutting the soundhole. What about reeds? for concert pitched sets I have seen sublimely finished reeds that sound pretty awful to a raggedy looking thing that blew the others away. They’ve been soft and quiet. They’ve been loud and abrasive. Some have refused to speak altogether! What I’m trying to say is, that regardless of any standardization, variation will not go away. Even in the event of high level production it will exist between companies.

Recommendations: For now, in terms of standardization of the Uilleann Pipes I think we might be in a holding pattern on the verge of finally touching down. (lets hope not in flames!) I believe that the pipes may be in a state that I recognize from the flux period in the early eighties that existed for the Hammered Dulcimer. The advent of a highly produced instrument left the most conscientious of skilled makers to do the custom work. i.e. People who knock themselves out and spend years developing and learning from established makers. Leo Rowsome is a good for-instance as evidenced in Patrick’s article. He was the standard of the day because he came very close to high level production (I heard 80 full sets in his lifetime. If anyone knows for sure I would, as a matter of interest, love to know) But I have to ask. Where did he

29

get his standard? Did he copy or did he develop his dimensions from experimentation. I ashamedly don’t know much about the man, but would like to (a definitive biography is in order, if it doesn’t already exist). The dissemination of information, in my eyes, is always the best policy. If we are to come to a consensus as to what a good chanter dimension should be, each maker should have available as many measurements as possible. I believe that if such information was free to all pipers they would, still, each ad their own nuance. But they would eventually evolve into something fundamentally similar.

Another way of looking at the problem of standardization is to demystify the instrument. The old adage “You don’t play the Uilleann Pipes, they play you” is clever and somewhat true. But, that should be qualified by a serious “But, it’s not impossible and it is mostly fun”. I have even been told that there is no intermediate player on the Uilleann Pipes. Is this the only instrument in the world that is privileged to have only advanced and beginning players? I have little hope myself of ever becoming an “advanced” player so, I would be happy with intermediate. If my only hope were to remain a beginner the rest of my life on the pipes, I would never have taken it up to begin with. Our mission as it stands is to popularize the instrument and take away some of it’s intimidation. And any standardization will build from there.

(Addendum 1/13/94: The oboe is standardized and mostly made by large companies. You can buy good oboe reeds at any comprehensive music store. But most professional oboe players still prefer to make their own reeds. I resign myself to the apparent, that double reed conical bore instruments are just difficult to reed.)

30

The Uillean pipe meets its grand-dad the pastoral pipe at the McCandless home around Pipers’ Day. Shown are Brad Angus and Brian struggling through a version of the Blarney Pilgrim. Mike MacNintch was in attendance sipping Newcastle and snapping the shutler.

31

The Scottish Traditional Music Trust by Gordon Mooney

A bagpipe collector in Montreal from Wales, a 16th Century house in Galashiels, Scotland, a Town Planner who plays and researches bagpipe music, and a Poet who set up a museum on Roman History in Scotland – unlikely ingredients to a wonderful and exciting project in the Scottish Borders to establish the permanent display of the history and living traditions of Scottish Traditional Music of which a centerpiece will be the fabulous collection of bagpipes belonging to Alan Jones a native of Monmouth in Wales who now lives in Montreal.

The Scottish Traditional Music Trust has during its first year of activities run music courses, on piping, fiddle, clarsach and a bagpipe festival weekend with talks, workshops,dances and concerts. Its aims are to promote and foster appreciation,performance and development of the diverse musical traditions of Scotland at the historic and beautiful Old Gala House in Galashiels, in the equally beautiful Central Borders some 25 miles south of Edinburgh.

How did this come about? The guiding figure is Gordon Mooney, by profession a town planner but also a world famous piper and exponent of the Bellows bagpipes of the Borders of Scotland, a researcher into the music of Scotland and a promoter of this ancient and beautiful tradition. Over the years he had become acquainted with Alan Jones, an engineer, musician and enthusiastic collector of bagpipes and related music.He has amassed about 80 sets of pipes from Western Europe; including Scottish, Northumbrian, English, Irish, French, Italian, Spanish, and Macedonian instruments.

On a visit to Alan Jones’ Bagpipers Convention in Vermont, USA, Gordon happened to suggest that instead of Alan having a house full of bagpipe cases he should consider displaying them somewhere so that he could get some room in his house.

Back in Scotland, Gordon became acquainted with Walter Elliot, a Lad 0′ Pairts. Walter is a renowned authority on the archaeology and history of the Borders, and has almost single handed brought international notice to Trimontium, the Roman military complex near Melrose. Walter had set up a trust and raised funds to mount a permanent exhibition of Roman history in Scotland in Melrose.

Walter also writes poetry and song lyrics and it was during a collaboration to produce a show for the Borders Festival that Gordon mentioned to Walter the collection of bagpipes in Canada. Walter suggested to Gordon that he should talk to Ian Brown the Ettrick and Lauderdale Museums curator, as the Council had a beautifully renovated 16th Century house in Galashiels wanting something to be displayed in it.

So a meeting was convened and a Scottish charitable trust formed, this being the first step towards the longer term goal – the Trust was honoured that the Duchess of Buccleuch a great supporter of the Arts in the Borders agreed to be the Patron.

The Trust at first organized music courses on fiddle, pipes and clarsach and obtained a small grant from the Scottish Arts Council as seed corn money to assist administrative costs. A small number of donations were also gratefully received.

In October 1993 as part of the Borders Festival a weekend of Traditional music making was planned.Part of this weekend featured a convention on Bagpipes … Could Alan Jones’ collection be brought over to Scotland to display at Old Gala House? What an idea!

It is still difficult to believe that it actually happened and after much frenetic work on both sides of the Atlantic, Alan’s collection arrived safely in Galashiels amidst a blaze of TV and newspaper publicity.Thanks to a grant from the Quebec Government to allow Alan to perform in Scotland he was also able to attend and take part in what was a great and exciting weekend, with representation from allover the UK, and wonderful music from Northumberland, the Borders, the Scottish Highlands, England and Hungary.

The bagpipe exhibition was fabulous, with all those examples of beautiful craftsmanship on view in the complimentary ambiance of the wonderful old Scottish House with its painted ceilings and eccentricities. It was much praised and visited and will go on show again for the summer months during 1994.

What is exciting is how much was achieved in such a small time and how much support and enthusiasm there is for this project and Scottish music. However to develop the project further the Trust would welcome sponsorship and/or donations to help set up a permanent Centre for Scottish Traditional Music at Old Gala House and install an exhibition of instruments and historical information and also to develop a series of educational courses and lectures.

For further information on the work of the trust and how you could help please contact Gordon Mooney.

33

REVIEWS

Shores of Lake Champlain, Original and Traditional Celtic Music

Review by Michael MacHarg

Featured artist Viveka Fox, Scottish fiddler extraordinaire with Christopher Layer (Scottish smallpipes, flute, bass and whistle), Jeremiah Mclane (accordion), Keith Murphy, Jim Baker, and Rick.

I received this tape as an advanced copy from Christopher layer. The tape was recorded in Vermont by musicians all living in Vermont – a trend I like to see, traditional music recorded at small local studios. The tape is a true piping delight, having a good number of traditional Scots and Irish tunes as well as newly composed tunes in the traditional style. There are many outstanding pieces on the cassette such as Mountain Road, Father John MacMillan of Barra, Cutty’s Wedding, An Oro, Johnny McGill, Cameron MacFadyen, and many more. I would highly recommend the tape to those with an ear for traditional tunes. You can get a copy from: Mountain Road Music, Viveka Fox, Box 1715, R.D. 1, Vergennes, VT 05491

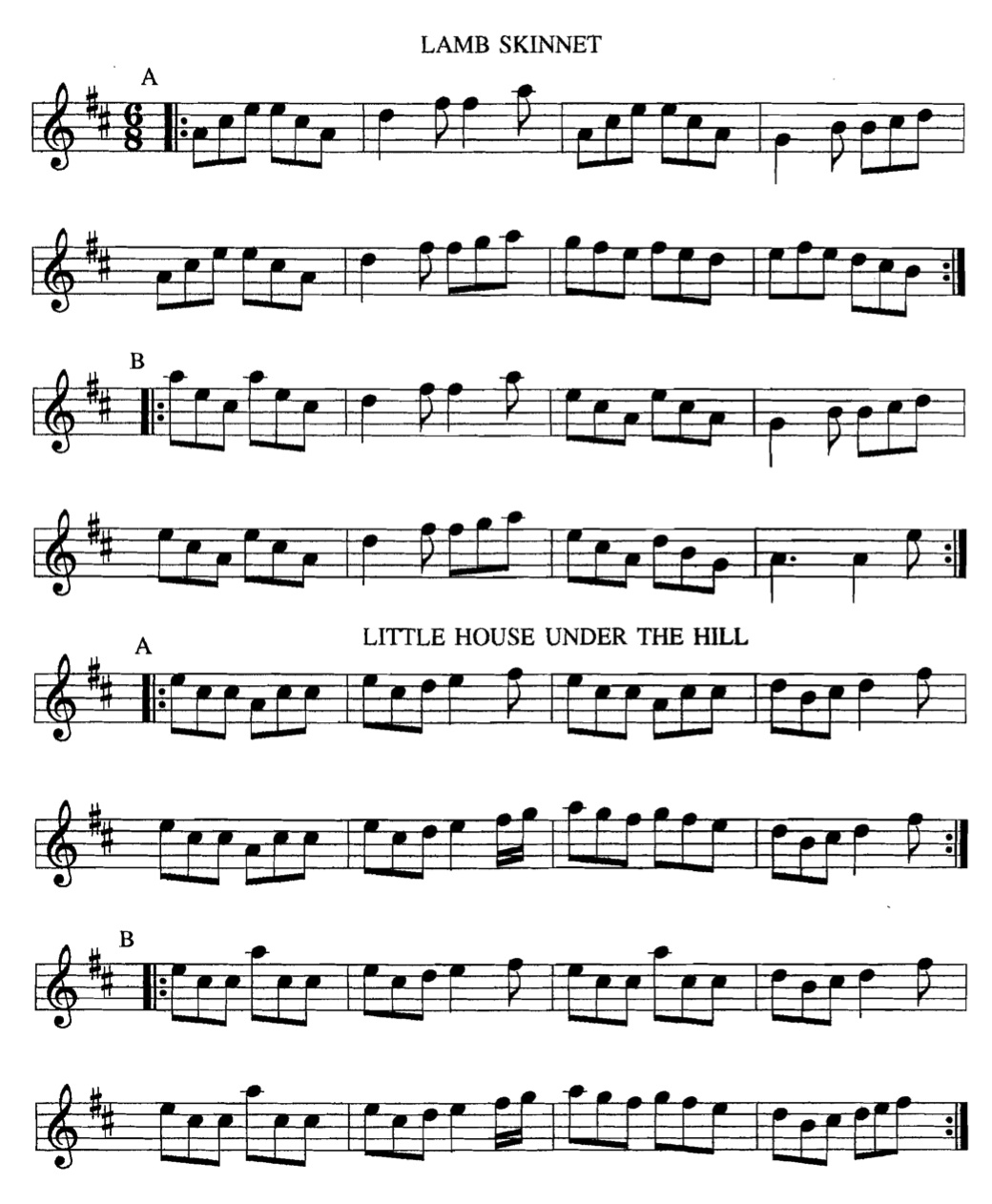

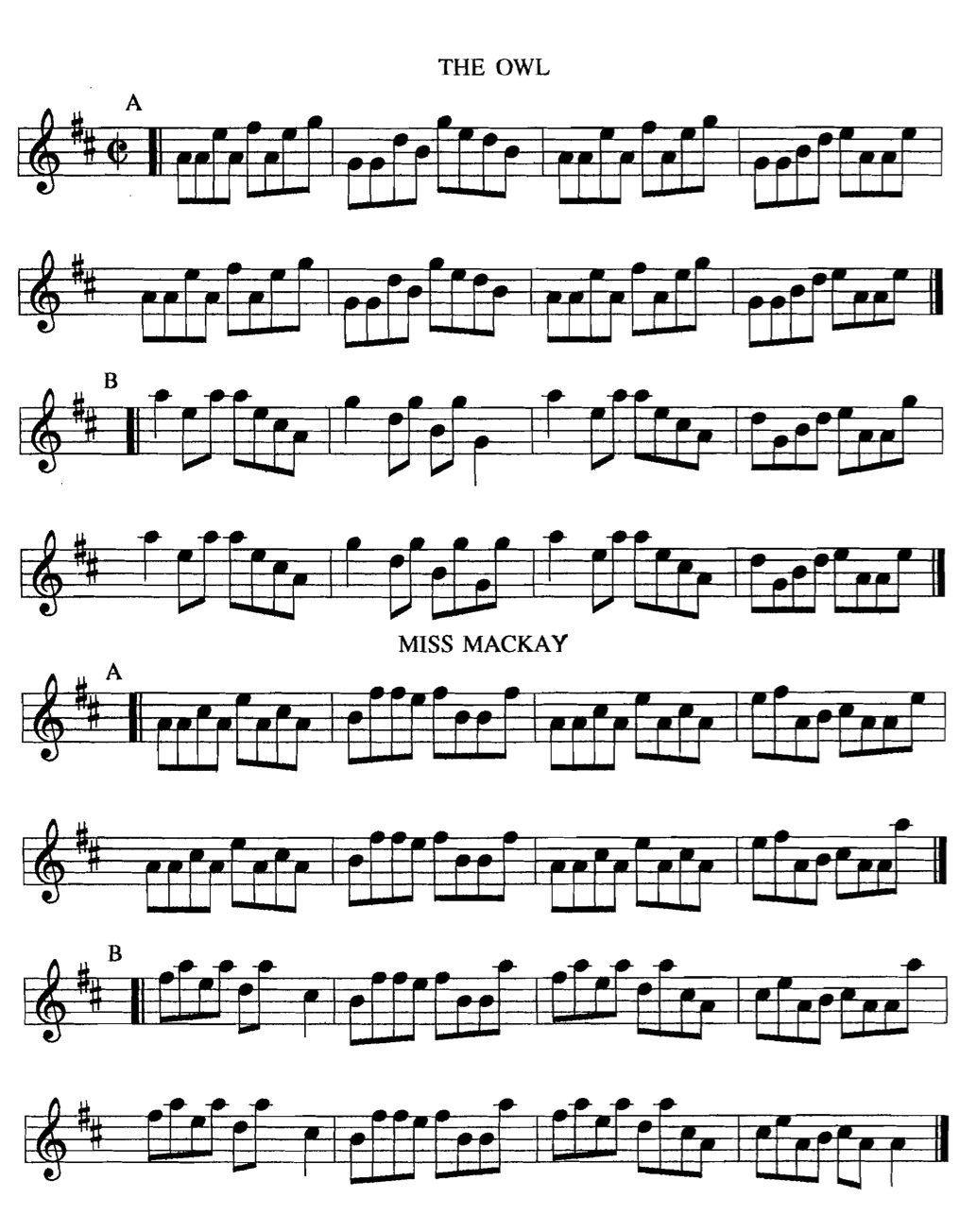

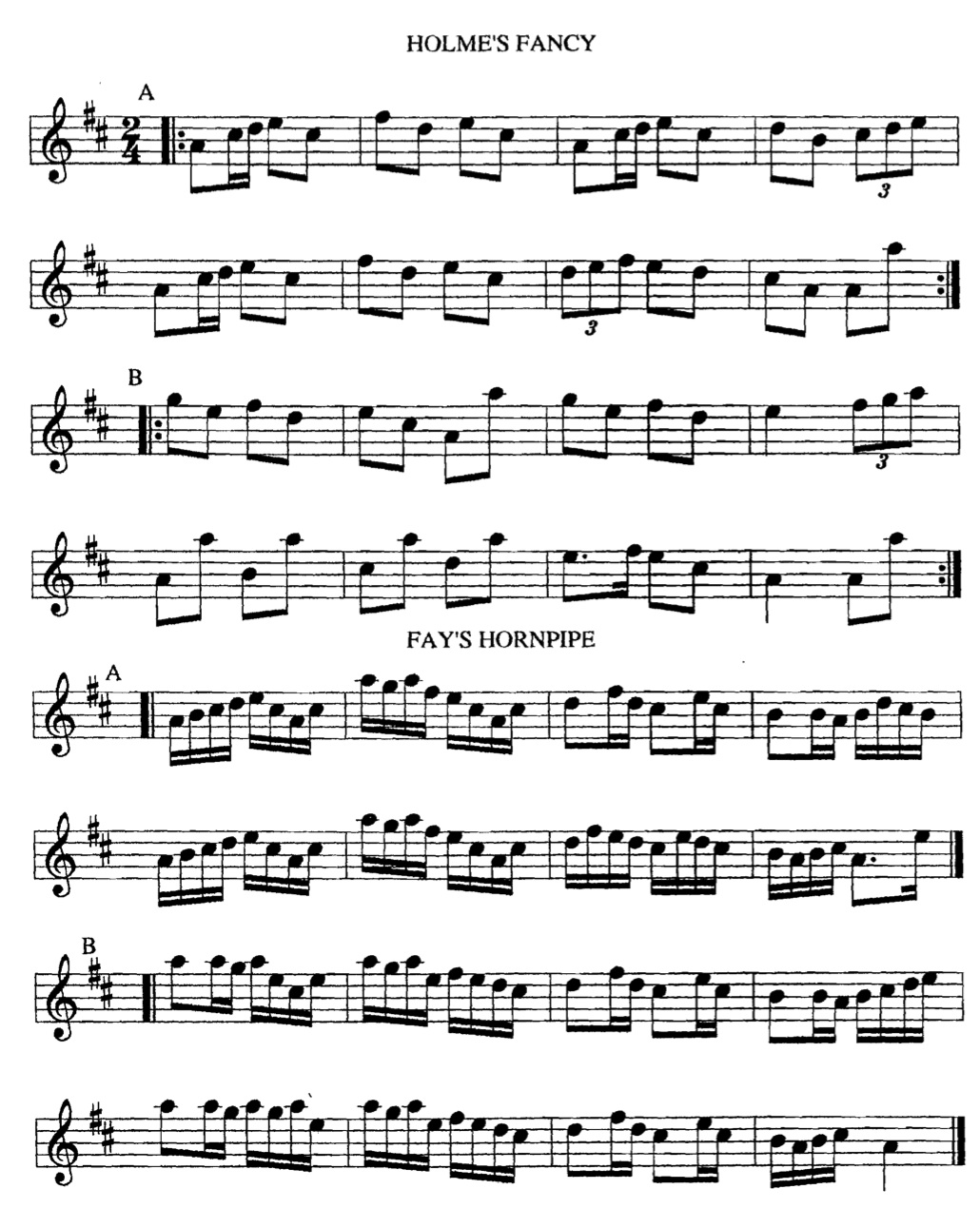

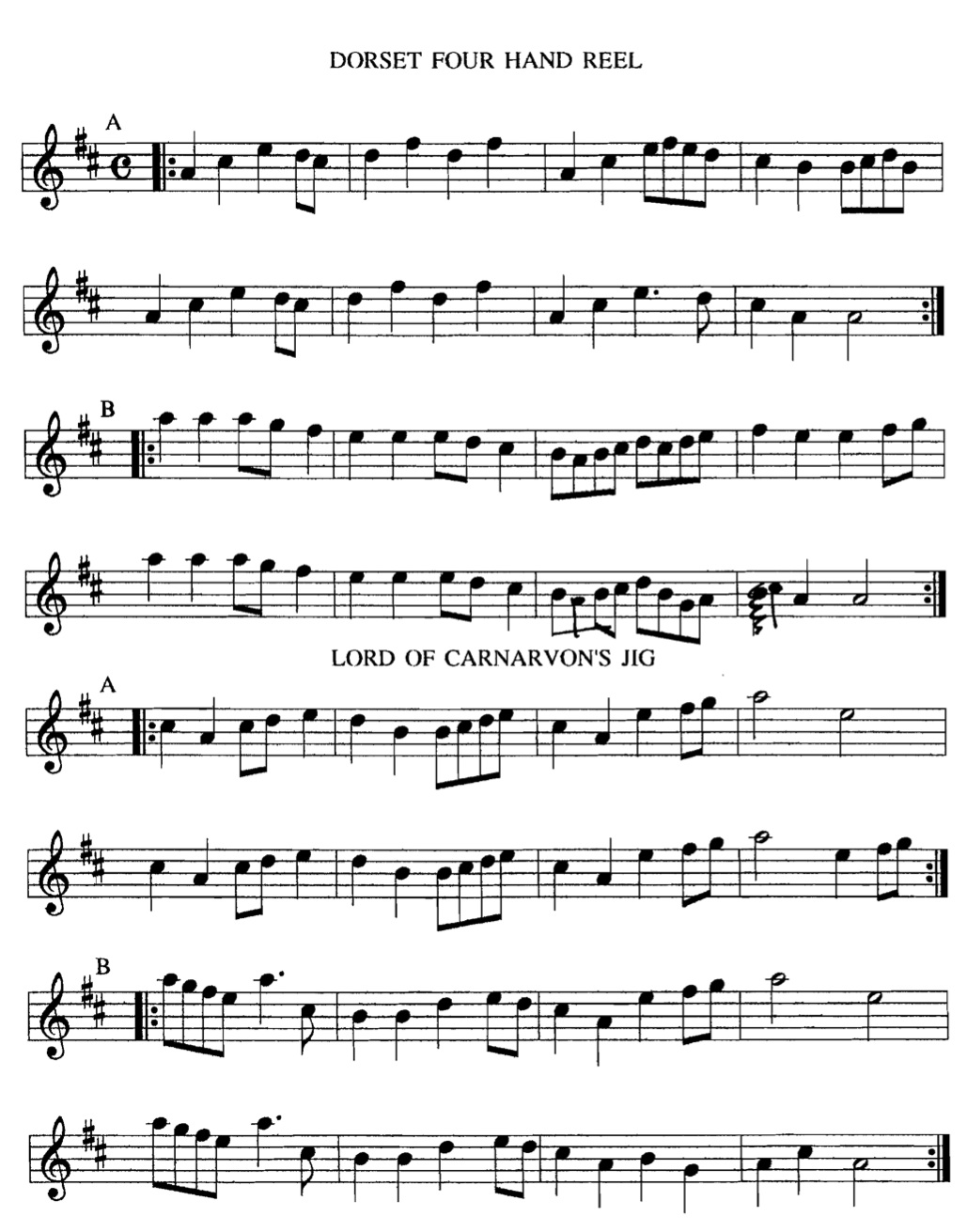

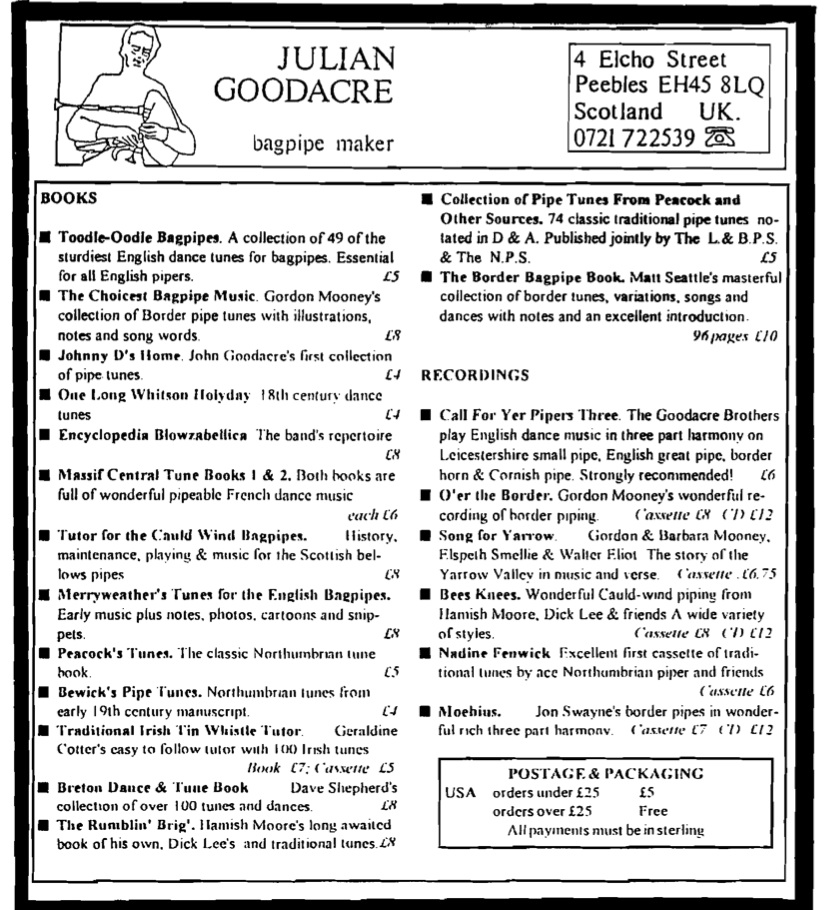

Toodle-Oodle Bagpipes, A First Collection of English Bagpipe Tunes, Chosen by Julian Goodacre

Review by Brian McCandless

If you’re tired of raiding and transposing “pipable” tunes from collections like John Playford’s English Country Dancing Master, then Toodle-Oodle Bagpipes will be a friendly addition to the pipe case. The small format booklet contains four dozen and one tunes drawn from a mix of traditional English country dancing sources and from the playing of some of Julian’s acquaintances, including a version of “Galopede” taken from a 19th century barrel organ. All of the tunes are neatly hand written two or three to a page and are arranged for playing on pipes with a D tonic. Thus the gamut is that of the Scottish smallpipe, Leistershire smallpipe, English great pipe in D, Cornemuse in 20 pouces (D), Uillean pipe in D, Pastoral pipe in D, and so on. If you are accustomed to the scale of the Highland bagpipe, just mentally shift your sights so that the space below the staff becomes A instead of the second space within the staff. These are fun tunes and we thank Julian for assembling this little gem. To obtain a copy, and for a complete catalogue of goodies, write to: Julian Goodacre, 4 Elcho Street, Peebles, Scotland, EH45 8lQ, United Kingdom.

The History of James Allan – The Celebrated Northumbrian Piper – 250th Anniversary Edition, by Alan BrignulI

Review by Brian McCandless

This little gem arrived as a gift from Julian Goodacre, and I had heard about it from Alan Jones but had never seen it. It is a diminutive booklet produced with the assistance of Newcastle City Libraries which documents the life of James Allan, whose portraits have graced many books and even the pages of our Journals. In its 20 or so pages it describes his life from “Gipsy” beginnings to playing for the Duchess of Northumberland. His later exploits of poaching, playing and stealing are well described. The booklet, first written in 1981 and reprinted in 1984 is available from Julian Goodacre at the address above.

34

REVIEWS (continued)

Reed Design for Early Woodwinds (Indiana University Press, 1992), by David Hogan Smith

Review by Eoghan C. Ballard